This page describes basic information about the Missing Children Affair. It also provides the political, social, cultural and economical background of the period. The videos below are samples that represent thousands of cases of which many were recorded.

Also in the Jews of Yemen Docuweb:

A Brief Background

A Brief Background

About Yemen

________________

Personal Stories

Personal Stories

________________

Operation 'On Wings

of Eagles'

________________

Early Immigration

Early Immigration

________________

Yemenite Jews &

American Colony

________________

Customs, Culture and

Customs, Culture and

Folklore

________________

Kinneret and Yemenite

Kinneret and Yemenite

Pioneers

________________

Relations with

Relations with

their Local Neighbors

________________

Missing Children

Affair

_______________

When did the Jews

When did the Jews

Arrive in Yemen?

________________

Links with

Links with

Other Jewish Centers?

________________

Jewish Scholars

Jewish Scholars

of Yemen

________________

| The Missing Children Affair

Who were the missing Yemenite children?

The missing Yemenite children were babies who disappeared upon their arrival to Israel with their parents, or shortly afterwards. The children generally disappeared from the baby nurseries in the immigration camps, from children care homes or from hospitals. It is important to note that babies of parents from other countries also disappeared, although there was a much lower percentage. People also refer to this case as “The Yemenite, Mizrahi and Balkan Children Affair”.

When did the babies disappear?

The majority of the babies disappeared between 1949 and 1954, although there are cases registered before and after the above dates.

What do we know so far about what happened?

This question does not have a complete, clear or fully satisfying answer.

The problem of the missing Yemenite children during the early years of the state of Israel left a wound in the Israeli society that still has not healed.

Parents, whose children disappeared, did not accept the administration’s answers. They passed their questions and their search on to the next generation. The new generation did not get sufficient answers during their quests. They forwarded the mission to a third generation…

Non-profit organizations looking for answers

At the end of this page you will find links to ‘Amram’, ‘Achim Vekayamim’, and Achim Achai (My Brothers) forum, which are non-profit organizations and forums. They are dedicated to exposing the truth about this affair.

These entities collect testimonies, materials, and DNA tests from families who experienced this tragedy. They are requesting that the authorities expose all archived material that is still closed, as of now, until 2066.

Yafa’s brother disappeared soon after her family arrived to Ein Shemer Immigration camp. Since then the family has been searching for him.

Background Context – The Period of the Missing Children Affair

The modern State of Israel was born in 1948 with a population that included about 650,000 Jews.

Intensive waves of refugees from Europe after the 2nd World War overwhelmed the country, as well as hundreds of thousands of refugees who fled Arab countries. This made it difficult for the State to organize decent absorption.

Political

The UN General Assembly adopted a resolution to partition mandatory Palestine between the Jews and Arabs on the 29th of November 1947...Following this, Britain terminated its mandate of the territory and completed a full withdrawal by the 15th of May. At midnight on the 14th of May, 1948, Israel declared itself an independent state. However the surrounding Arab nations did not accept the UN resolution and Israel was forced, at the same time, to prepare for war.

Indeed, five Arab countries attacked the young country from north, east and south. After a few months of intensive battles, they signed ceasefire agreements in 1949, with lines that became the temporary borders of the state.

Due to the war of independence, the 1st democratic elections were postponed from October 1948 to Jan 1949. Twenty one political groups signed up. As a result of unbridgeable disagreements among the members of the groups, the existing temporary assembly ended up as the first parliament prior to the general election.

The majority in this parliament were secular, socialist, Zionist members who came from central-eastern Europe. These members had within themselves conflicts regarding which political and social direction the country should take.

The government included labor, religious, progressive, Sephardic, and minority parties.

Economic

During its early days, the state of Israel faced a number of challenges...The relatively small Jewish population, about 650,000, had to sustain itself, to keep on with life, to supply education and social services, to fight the war of independence, to absorb hundreds of thousands of holocaust survivors, and to rescue the hundreds of thousands of refugees who fled the Arab countries. All of these needed resources which were lacking in the young country.

Indeed economic activity flourished during the British mandate period due to a need for supplies for the British forces and for the growing population. But the toll of the missions was far beyond the ability of the young country to carry alone.

In 1951 the country faced an economic crisis which almost resulted in collapse. The government took tough measures. Among them were an economic austerity policy and imposing higher taxes. For a short period, it also put a limit on immigration to the country. Unemployment grew and many immigrant families who could not cope with the tough economic environment left the country.

Some actions were taken to bring foreign currency into the country, such as: selling government bonds abroad, negotiation with Germany about reparation for holocaust victims, a request for aid from the United States. Although the actions taken during those years improved the economy, still the basic characteristics of the economy were left without a major change. It was a centralized economy, with weak private sectors, low labor productivity and a small amount of capital investment from outside the country.

Social

The waves of immigration from dozens of countries introduced a wide range of social problems in addition to the economic challenges. Among them; communication issues due to language barriers, cultural differences, educational differences, different codes of behavior, and many more...Out of the existing Jewish population at the creation of the State in 1948, the majority were what was defined as Ashkenazi Jews. The rest originated primarily from Muslim countries or were decedents of Jews who had resided in the area for numerous generations. A large portion of the established population was secular, which wanted to maintain the new culture that it succeeded to create in the country – a culture with a European flavor. This meant integrating all incoming populations into this secular European-style culture.

This policy, initiated by the leadership in the country, depended on a process of socialization. It was actualized intensively by the office for absorption, by the education system and in the army.

Assimilation

In order to assimilate the immigrants into the social and cultural reality, the administration treated their culture as something insignificant – not as important. In practical terms, it conditioned the offering of jobs or accommodations on political support. It almost always ignored the individual needs and wishes of the immigrants.

This created an unhealthy type of relationship between members of the existing population and the new immigrants, mainly those who came from Muslim countries. When this was accompanied by terminology that expressed negative stereotypes – like backward, uncivilized, reluctant to work – it intensified the process of unrest and tension in the Israeli society.

The level of pressure on the immigrants to desert their culture eventually diminished in time after the establishment realized the consequences.

Waves of Immigration

There were a few waves of immigration to the country after the declaration of the State. The first were mostly the illegal immigrants who were arrested and moved to Cyprus detention camps by the British during its mandate in Palestine. This wave, in 1948, included about twenty-four thousand immigrants.

The second wave was made up of those survivors who gathered in the DP camps in Europe after the Second World War and included about 250 thousand Jews.

The third one started in 1949. It was the wave that brought the Jews from Muslim countries. By the end of this wave they amounted to about 53 percent of the total immigration. By the time of the third wave the absorption facilities, such as immigration camps and deserted British army camps, were overflowing. There was a need to supply the newcomers with emergency accommodations.

Temporary camps of tents and sheds were built across the country. They provided poor facilities, a lack of sufficient services and were a base for problems that rose shortly afterwards. The intention was to use these camps, later known as “the Maabarot”, temporarily. However, it turned out that they served most of the immigrants, primarily those who came from Muslim countries, for quite a few years.

Most of the immigrants from Europe moved on within a few months due to preferential treatment. This is based on statements given years later by some of the officials of that time. Others left after receiving reparation money given to families that survived the holocaust. The next wave started at 1956 and kept on for a number of years.

Immigration of Yemenite Jews

The operation to bring the Yemenite Jews to Israel was called 'On the Wings of Eagles'. It began in late 1948 and ended in 1950. As part of this, about 42,000 immigrants arrived to the country.In the series of follow-up operations, which continued until 1956, several thousands more arrived. The total number of immigrants from Yemen in the first years of the country reached almost 50,000 people, in addition to the 40,000 who had immigrated intermittently since 1881.

After the main rescue operation, the immigration continued over the years with small groups and families that amounted to a few hundred immigrants.

The immigrants arriving in the early years of the country were housed in camps spread across the country. The Yemenite immigrants were directed into 4 separate camps, located in Atlit, in Pardesiya (sub-camp G), in Rosh Ha’ayin and in Ein Shemer (in both sub-camps A and C).

The explanation presented by the Integration Offices for this separation, was that it stemmed from special needs of this aliyah.

Conditions in the camps

The immigrant camps were intended to serve as a quick temporary solution to the waves of immigration to Israel in the first years of the State. Living conditions in these camps were difficult...The immigrants lived in tents and huts, densely crowded into a limited area with poor sanitation. The inhabitants were sustained on a minimum diet and received inadequate medical care. Added to this were language communication difficulties, the differences in mentality, and lack of educational infrastructure.

The need to reduce the immigrant’s dependence on the system, as well as the desire to expand settlement, led to a government policy to move immigrants based on employment requirements, both near where they lived and throughout the country.

The initial camps were soon transitioned into semi-permanent neighborhoods with less government intervention. Many of the families were transferred to other locations in order to integrate them into a required workforce and some were transferred to new or existing agricultural settlements.

The responsibility for the absorption of the immigrants in the camps and later in the semi-permanent neighborhoods was in the hands of government agencies headed by the absorption department.

Services were provided to the families such as overseeing health issues including early child care. A key role was played by the “Immigrant Medical Services” which was established at the end of World War II to care for Holocaust survivors.

The care of infants and young children

Three factors in the camps were related to the care of infants and young children. Their relationship was consistently interconnected.

- “Immigrant Medical Services”: Divided into two main districts: Northern District – located in Haifa, and Southern District located in Tel Aviv. The service was responsible for setting up medical institutions in the camps, recruiting personnel, and providing equipment.

- The Jewish Agency’s Absorption Department: It had a number of wings, including the Camps’ Division, the Social Wing Division, and the Yemenite Immigrants’ Division.

- Zionist women’s organizations: among them WIZO and Hadassah, which were founded abroad, as well as women’s organizations associated with political parties in Israel, especially the Working Mothers’ Organization and the Mizrahi Women’s Organizations

The Yemenite Immigrants’ Division of the Agency’s Absorption Department included several dozen veteran Yemenite immigrants who were deployed as an auxiliary force in the camps. Its job was to link the various absorption factors and advise on matters related to their absorption.

The Case

The Case relates to the disappearance of small children of newly arrived immigrants to the country. It has come to be known as ‘The Yemenite Children Affair’ since the majority were from the Yemenite community. However it also includes children from other communities.

When did children start to disappear?

The disappearance of infants and young children in small numbers began as early as the 1920s. By 1948, about 115 cases had been reported. The surge in immigration with the establishment of the state turned the phenomenon into a massive event in which, according to available information, about 5,000 babies and children disappeared. The phenomenon diminished with the dwindling of the great waves of immigration.

Between 1955 and 1980, about 355 children disappeared. The phenomenon gradually subsided and ceased in 1980.

The main characteristics of the disappearances of children during the period of the great immigration were:

- Most of the missing children were from families of Yemenite descent, the rest were children of families from the Balkans and other places in Europe

- Most of the disappearances occurred around the time of arrival to the country

- The children usually disappeared from baby care homes in and out of the camps, from hospitals, and from medical and welfare institutions of the Zionist women’s organizations (WIZO and Hadassah)

- The families were informed of a sudden death, with no apparent medical reason

- In some cases more than one child from the same family disappeared

- Babies sometimes disappear immediately after birth

- In some cases babies were taken from their families by force

- In some cases, people from the agency’s absorption system were involved

- The families did not see a body, did not receive documentation and did not receive details about the burial

Where did the children disappear from?

According to the testimonies of a significant number of the families in the State Commission of Inquiry, most of the disappearances of the children took place in medical and welfare institutions. Several dozen institutions from all over the country were involved. These included government institutions, the Agency, the JDC, the Histadrut, local authorities, as well as the women’s organizations.

In most cases it was possible to determine the starting point where the missing child was first hospitalized, and to show that most of them were transferred from the medical facilities in the camps to the hospitals outside of the camps. According to the testimonies of some of the members of the absorption system, in many cases children were later transferred from the hospitals to the children’s institutions of the women’s organizations.

Yona’s baby brother, Yihye, was 7 months old when a nurse took him, by force, from Yona’s arms.

Establishment’s explanation for the disappearance of the children

Eventually, the establishment and the Examination and Inquiry Committees tried to explain the phenomenon as stemming from 3 different reasons:

1. Medical – claiming that the immigrants from Yemen arrived in a worse medical condition than groups of immigrants from other places.

2. Organizational / bureaucratic – claiming that this resulted in, among other things, a disconnection between the parents and their children who were transferred to remote medical institutions without the parents’ ability to reach them.

3. Demographics – claiming that the families of the immigrants from Yemen were blessed with children and the parents did not have the ability to take care of them properly.

Disappearance of children in other countries

It should be noted that the disappearance of children in the country, in the early years of the State, is a phenomenon that also, unfortunately, occurred elsewhere in the world. Forced transfers of children from politically, economically, socially weak populations to more established populations occurred in many countries, also in peacetime.

Such events began as early as the end of the 19th century and continued more intensely against the background of World War II and its demographic, economic and social consequences. Then there was also a great demand for children for adoption, which led to the formation of a developed market. This activity took place in countries such as England, Switzerland, Greece, Ireland, Spain, the United States, Canada, Argentina and Australia. Its exposure occurred only after decades of denial and silence.

An open wound for all

The majority of the population that came to Israel in its early years was mainly characterized as a refugee population that came from both Europe and Islamic countries. Everyone experienced the difficulties in the early years. Some experienced this more than others. The issue of the disappearance of children, experienced mainly by Yemenite Jewish immigrants, remains an open wound for all, both morally and due to the fact that precisely here, where it was supposed to be the safest refuge for them all, they experienced the most shocking tragedy.

It was a population that abandoned, in many cases, all of its property in Yemen. During their journeys out of Yemen, which lasted many months, they were cheated, robbed and physically depleted. Before they had recovered, for the most part a few days or weeks after their arrival, they lost loved ones. Some as a result of disease, but some as a result of unexplained disappearances.

The video above contains a collage of stories of five families who tell their own experience regarding the so called ‘Missing Children Affair’. These families immigrated to Israel from Yemen, other Arab countries and the Balkan areas. They were part of the big waves of immigration that flooded the country during it’s early years of existence.

When was the case of the disappearing children exposed

The public media did not often deal with the issue of the children who disappeared over the years. Complaints and articles on the subject appeared occasionally but there was not enough public resonance. Personal initiatives for the discovery of the missing were taken by the families, immediately upon the disappearances and years after. They were not assisted by an economic and / or administrative home front. It was assumed that this was a phenomenon of individual private cases.

The snowball began to roll in the mid-1960s when family members began receiving army recruitment orders for their missing children. Only then was it acknowledged that it was a large-scale phenomenon with cases that had a regular pattern. The individual activity of the families transformed into group activity which followed by a setup up of the “Public Committee for the Detection of Missing Yemeni Children.”

Eventually, in an attempt to deal with the public pressure on the issue of child disappearances, the Israeli government decided to set up a parliamentary inquiry committee. In fact, so far 4 committees have been set up regarding this issue.

Inquiries and Investigative Committees

Two inquiry committees and one investigative committee were set up to clarify the allegations.

- Bahlul-Minikowski Committee. (1967) – An inquiry committee that was appointed, discussed about 340 cases. In light of the harsh criticism it endured following its conclusions, another committee was established.

- Shilgi Committee (1988) – A review committee that discussed about 505 cases. A large number of them were a re-examination of cases discussed by the previous committee. It submitted its conclusions in 1995. This committee also suffered criticism, after which another committee was appointed. This time it was an official state investigation committee.

- Cohen-Kedmi Committee (1995) – a state commission of inquiry that examined about 800 cases, about half of which were in a previous examination. This committee submitted its conclusions in 2001. Like the previous committees, it also determined that the vast majority of the children did die. The investigative materials of this committee were subject to 70 years of confidentiality. This confidentiality was lifted in 2017 following a request made by then-MK Nurit Koren to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Still there was a claim, with solid roots, that not all the committees’ investigation material was released.

The criticism against all three committees included allegations that they too easily adopted documents and testimonies about the deaths of the children. They claimed that the Kedmi committee “… ignored the extensive information in its possession and it did not receive thorough and professional treatment. Because the committee members adopted documents without verification, did not investigate things in depth, discrepancies and inaccuracies were discovered. It was not clear how they (committee members) reached their conclusions … “

Parliamentary committee

Following the criticism, a special parliamentary committee was established:

- Committee headed by then-MK Nurit Koren (2017) – The minutes of this committee are open to the public as well as its meetings. On her own initiative, the investigation materials of the previous examination / investigation committees were exposed. The Temporary Provision Law (limited to two years) was enacted to expose graves defined as those in which missing children were buried.

Also a DNA bank was created for members of families of children who disappeared. This was for the purpose of matching the results with the DNA of the children in the graves, if found. This special committee collected testimonies from families whose cases were not recorded before.

Three opinions about the missing children affair

Currently there are 3 positions related to what actually happened in relation to the issue of missing children.

- The first position’s claim is that things never happened.

Most of the children died except for a few isolated cases resulting from human error, including confusion in names and dates of birth. This, they argue, was the result of defective administration and the like. There is no room for a conspiracy theory. According to this position, the several dozen cases where there was no proof of death could be explained by the occasional delivery for adoption. All three appointed committees supported this position. - The second position’s stand is that there were indeed cases of illegal adoptions without the knowledge of the parents, but that there was no institutional plan here. Rather, it was a phenomenon conducted in parallel, without the knowledge of the institutions, which turned a blind eye as a result of institutional indifference. This reflected a prevailing atmosphere that such adoptions actually help to procure a better future for the children, who came from underprivileged families.

- The third position claims that there was an organized institutional activity initiated from the highest places and that its essence was the transfer of children for adoption both in Israel and abroad. To achieve this purpose, a mechanism involving entities in and out of Israel was activated.

The third position was represented by Rabbi Uzi Meshulam (1952-2013) and his group. Rabbi Meshulam was the founder and head of the “Ateret Zakanim (crown of the elders) – Mishkan David” yeshiva. He initiated a wave of protests in 1994. This wave eventually led to the establishment of the State Commission of Inquiry and the Cohen-Kedmi Committee (1995).

A number of non-profit organizations support this position.

Dr. Nathan Shipris, a historian, also presents this position in his book “Where have All The Children Gone?”. This seems to be the most comprehensive book, so far, which has been written on this affair.

The book, published in 2019, is the product of research that he began as a student. He started it as he became acquainted with the affair and the perpetrators of the wave of protests. The total number of complaints of cases of child disappearance, according to Dr. Shipris as of the time of publication of the book, is 2050. That is, more than double the number of cases that were before the State Commission of Inquiry, the Cohen-Kedmi Committee.

Neomi Oshri baby brother was taken by force from his mother. When the father looked for him in the hospital, they told him the baby was gone.

Some testimonies from the examination / inquiry committees

Families

Summary of testimonies given by members of 6 families from the protocol of the Cohen-Kedmi investigation committee (physical ID. 9746/13-ג), date of session 30/11/1995...Zohara Tzfira – File 308/95 pages 4156-4172, Summary

Zohara came to Israel in 1949. She arrived in Rosh Ha’ayin immigration camp, then was moved to Ajur. From there she was transferred to Habad Village where she gave birth to a baby girl.

Both mother and the baby did not feel well and were taken to a hospital. The next day the mother was released and the daughter was not. They told her that she didn’t know how to treat the baby. Her crying and begging didn’t help even though she had already raised 2 children. The mother would come daily to try and take the girl but they would not give the baby to the parents even though the child looked healthy.

From the hospital, after a few weeks, the baby was moved by force to a baby care center of the Agency in Be’er Yaakov. There, they also would not give the girl back to her parents.

Neither in the hospital, nor in the baby care center, were the parents allowed to visit the baby girl in her room. They were allowed to see her only through a window.

One evening the parents went to visit the baby. She was drinking milk and laughing. The next morning they told the parents that the baby died. The body was moved to the hospital in Tzrifin. The parents were shouting and crying. They showed the parents a body of a girl about 2 years old. The parents claimed that it was not their child since their child was only 4 months old. They could not accept it, and felt helpless, despaired and did not know what to do. The body of their child was never shown to them.

Years past. The girl, Mazal, received a call-up letter from the Army. The parents went to the recruiting office hoping for a miracle. There, after the parent’s inquiry, the recruiting personnel changed the name in the document to Nehama.

The parents still, at the time of the testimony, did not see a grave, and did not believe that their baby girl died.

Shalom and Saada Koresh – File 309/95 pages 4172-4188, Summary

Shalom Koresh and his wife arrived to Israel from Yemen in 1949 and were placed in Beit Lid immigration camp. In 1953 they moved to Gordon suburb in Rishon Letzion.

Their baby disappeared four days after he was born. Shalom visited his wife and the baby daily in the hospital. Shalom said they told him “You have a beautiful child”. Four days after giving birth, the mother was sent home without the baby. They told her that the baby should stay, that he would be moved to WIZO for a few days to gain more weight.

They told her to go to WIZO. Shalom went back requesting his child. He shouted, cried and became wild. They threatened that if he created problems they would call a policeman and he would be put in jail. After that, he said that he was afraid since he had no work or anything. Shalom believed his son was alive. “Believe me” he said to the committee, “I saw him with my own eyes, my wife nursed him in the hospital…and then she came without a child”.

The father went to WIZO four times to inquire about the child. The fifth time they told him that the child died and that they buried him. The parents were not shown the body. They did not get a birth certificate, and they did not get an address of where the baby was buried.

Miryam Tzeiri –File 310/95 pages 4188-4201 Summary

Miryam arrived to the country with her husband and their children in 1938. They were sent to an immigration center in Aliya Street in Tel Aviv. She gave birth to twin baby girls in Hadassah hospital in Tel Aviv. The 1st girl weighed 2 kilo, the 2nd weighed 2.5 kilos. The mother was weak. After a few days she was sent to a rest home, close by, for her to be stronger.

The mother would come 3 times a day to nurse the girls. The medical crew told her that the girls were fine.

One day she came as usual and one of the girl’s beds was empty. “Where is the baby?” she asked the Doctor. The doctor pointed up. Mother Miryam went up the stairs to look for the baby. “It led nowhere”, she said. They called the manager of the hospital who told the mother that the girl had died and she didn’t know where the body was. She also said to the mother “…You have many children”. The mother said that even if she had 20 children she wouldn’t give up the girl.

The doctor, who was beside the mother, said in a low voice: “Again this evil was done”. The doctor told the mother later that both girls were healthy and strong. The parents never got any document about the missing daughter. No death announcement, no death certificate and no burial documentation.

Roni Eliyahu –File 311/95 pages 4201-4214 Summary

Roni Eliyahu came to testify about the disappearance of his 2 brothers, David and Rimon. The story was told by Roni as heard from his mother. The mother was present during the testimony.

They were 3 brothers: Roni was the 1st, Rimon the 2nd and David, the 3rd one, who was born in 1953.

Rimon was born in December 1952 in camp Gavava in Rehovot in the tent where they lived. The mother nursed him. The next day, a doctor with 2 nurses came to the mother and asked to let them take the child to Asaf Harofe’ hospital. “We will take the child, register him and then bring him back to you”. They did not.

The mother went to the hospital the next day and the day after, and the next after that asking to bring back the child to her.

A week later they told her that the baby had died. “Never mind” they told the 17 year-old mother, “You are still young, you will still bring more children, the baby died, go home, that’s it”.

Roni told the committee that he had a photo of himself with the new born baby brother. This photo, he said, was taken by the doctor and the nurses who came just after the labor. They said that it was a photo that would serve as a souvenir from the camps. This was the baby they took to register. Some time later they discovered that the date of birth of the baby was changed from December to May.

After David was born, there was a person in the camp who was a wheeler-dealer kind of a person. He had a car. His name was Daud Razal. According to Roni’s mother’s story, this man used to frighten mothers. He would go to a mother and would tell her that her child looked ill, and he would offer his service to take the sick child to the hospital.

The next day when parents would go to the hospital to bring their baby, they would tell them that the child had died. The same thing happened with Roni’s other brother, David. They told them in the hospital that the baby died. When they approached Daud Razal, he told them that the child had died, there was nothing he could do.

The parents searched for the child throughout the years everywhere they could. They arrived to the census office in Jerusalem, but there was nothing. They were only able to get some information through a friend in the Income Tax Office who was able to get into some files.

“I will tell you something that you should not share” he said. “Your brother is alive and exists in covert file number 7753 in Jerusalem”. The friend, afraid of loosing his job, could not give the parents a physical document as proof.

The family believes that both children were sent for adoption. They kept on with there lives. The parents raised, in total, 5 children apart from the two who disappeared.

Sara Saiid – File 314/95 pages 4214-4223 Summary

Sara Saiid came to the country in 1949 with her husband and their one-year-old baby girl. Upon arrival she was also eight months pregnant with her 2nd child. They arrived at Rosh Ha’ayin immigration camp. The family lived in a tent. Sara was taken to Dajani hospital in Jaffa to give birth.

Sara and the baby were taken to a Baby Home where she stayed with him for a week. Then she moved back to the tent and would come twice a day, morning and evening to nurse him.

This process continued for about 5 months. One evening she came together with about 20 other mothers to nurse their babies. She did not find her child in his bed. The other mothers also did not find their children. They looked through the other rooms wondering if, maybe, the children were moved.

The mothers reacted, creating a ruckus wanting to see their children but the mothers were not allowed to visit them. Sara said that she wanted the documents of the child. They told her that she should wait a month. They said that they would register him and then she would get the documents.

Regarding a visit, they said that in a month the mothers would be taken in an organized bus to visit them.

The mothers waited a month. The bus took them to Tzrifin camp where a woman called Sara Uzeri received them. They entered the sheds where the children supposedly were, checking against the list of children. None of the babies were there.

They told them in Tzrifin to check in Beer Yaakov. They arrived there. Sara Uzeri asked the mothers to stay outside. She went in to check. Then, she returned telling the mothers that each of the babies had died. As Sara Saiid described it: “No names, no death certificate, nothing”.

The mothers could not accept it. They started to cry and made a commotion in the bus. When they returned to Rosh Ha’ayin they said that they were not going to mourn since there was no death certificate and no grave and no documents at all. “They did this”, she said: “After they had told me that when I would be set, that they would give me the baby’s birth certificate… and would give me…”

“I called the baby Nahum,” she said: “God saved me when I fell off the camel on the way, and my husband said that god felt sorry for me and saved me”.

Sara’s older daughter was taken to a Baby Care center as well. One evening Sara and her sister in-law came to the Baby Home, broke the glass in the window, entered the room and took her baby girl. She would not let them take her again.

Shoshana Garame’ – File 312/95 pages 4223-4238 Summary

Shoshana Garame’, married to Nisim, was the daughter of Shulamit and Amram Shara’bi. She testified to the Cohen-Kedmi investigation committee telling the story of her missing sister Miryam, as told to her by her mother.

Her parents arrived to the country in 1948 with their daughter Miryam. They were transferred to the immigration camp in Ein Shemer where Shoshana was born. Miryam was a year and a half old when they arrived.

The mother was told to take Miryam to the Child Care center since the child suffered from diarrhea. The mother refused. As a result the food stamps were cut from the mother. For 3 days the mother was looking for food remains in the garbage, then she gave up, since she had two more children to feed and she was also a few months pregnant.

She went to the camp manager’s office. His name was Booki – “My Mother will never forget his name” said Shoshana. He got up from the table and screamed at the mother, telling her “Aren’t you ashamed? You have 3 children, the fourth on the way and you are still stubborn? Give the girl and you will get food. If you don’t give her, you will not get food”.

The mother, left with this dilemma, gave her up. She took the girl to the Child Care Center in the camp. They took the girl, put her in a room and would not let the mother come in. Two days later they told the mother that the girl had to be transferred to a hospital in Haifa. The mother was not allowed to go with the child. They let the father go in the ambulance, so the mother agreed. Before they left the immigration camp compound, they forced the father out of the ambulance and drove to Haifa. Three weeks later, they announced through the speakers in the camp that their baby girl died.

The mother did not believe that the girl died. No death certificate, no body, no grave. She remembered one volunteer woman in the airplane, when she arrived, telling her: “My daughter, keep your children, keep them close to you”.

“The girl”, said the mother, “had diarrhea because of new molars (teeth). She was a year and a half old – it happens also with children today that new teeth are accompanied with diarrhea…”

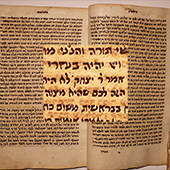

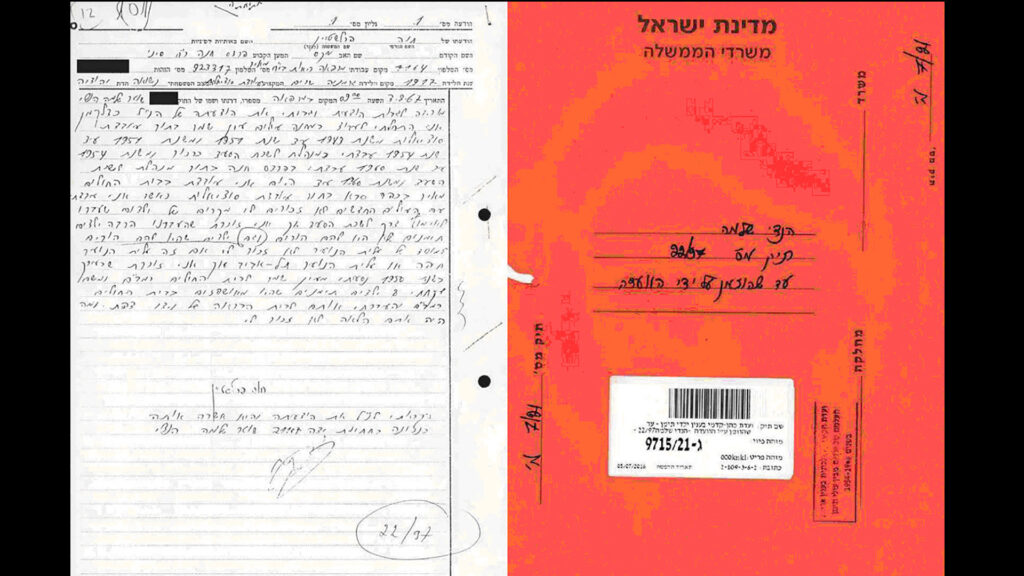

The full copy of the original protocol in Hebrew is displayed below

(this may take some time to load)

Social Worker’s testimony

Hava Perlshtein’s testimony, from Cohen-Kedmi Investigation Committee. File 22/97. 9715/21–(ג)...

…”I started to work in the “Ein-Shemer” immigration camp as a social worker from 1943 until 1951. From 1951 until 1954 I worked as the manager of the Welfare Office in Karkoor and from 1954 until 1960 I worked in Pardess Hannah as the manager of the Welfare Office there. From 1960 until now [1967 – date of testimony] I have been working in Meir Hospital in Kfar-Saba as a social worker.

When I worked with the new immigrants, I do not remember cases of children who were adopted through the welfare department. But I remember that we transferred many Yemenite children who had no parents, and also children who had parents, to an institution of the youth immigration. I do not remember if this was the youth immigration institution that was in Haifa or the one that was in Tel-Aviv. But I remember that at about 1950 I took 8 Yemenite children who were hospitalized in ‘Rambam Hospital’ (in Haifa), and transferred them to a recuperation house of WIZO in SAFED (Tzfat). What happened with to them later I do not remember”…

The above testimony was recorded by the Policeman Shlomo Handi on Aug 3rd 1967. Submitted to the Cohen-Kedmi Investigation Committee. File 22/97. 9715/21–(ג)

Doctor’s testimony

Dr. Amsted testimony, from Cohen-Kedmi Investigation Committee. File 301/96. 9750/11–(ג)... English translation ****** ****** Copy of the original protocol in Hebrew File 301/96. 9750/11–(ג)

Rabbi Shmuel Avidor Hacohen’s testimony

Rabbi Shmuel Avidor Hacohen Testimony from Cohen-Kedmi Investigation Committee. File 247/96. 9748/16–(ג)... pdf: 00071706.81.D0.B1.DB.pdf from page 8255 English Translation, pages 8256-8261 Rabbi Shmuel Avidor Hacohen: P.8256 In September 1963 I visited NY. In a meeting with some people, there was a couple. The woman originated in Israel, the man was American. With them, there was a girl, about 10-11 years old, maybe a bit older. By the look of the couple and the girl, it did not seem that the girl was their natural daughter. I asked quietly. They answered. Yes, that she was a Yemenite girl that they adopted in Israel. I started a conversation with them. I didn’t think that there was anything more serious there. They told me that they adopted her. And then they told me that there were more families that adopted Yemenite children. Somehow in the neighborhood there was the rumor about a person that already passed away, who was the organizer of these adoptions. I must say that it never dawned on me that these adoptions were not made on behalf of the biological parents of the children, but nevertheless, it looked very peculiar to me. It looked and still looks difficult [to understand] until now, that children that immigrated to Israel from Yemen, were being brought to America. [Unusual] enough that it would bother me. P.8257 When I returned back home (to Israel) I checked how and why and who. Here the establishments…I remember that I talked with Mrs Debora Eliner. She was in the Immigration Department of the (Jewish) Agency. I do not remember who else I talked with. Here, it was clarified to me that the establishments that deal with adoptions or giving children for adoption say that they know nothing about this matter (of children being sent to America for adoption). This surprised me even more – in so far as I had some names with me that indicated “this one has a boy, that one has a girl, and so forth”. I sent a memorandum to Minister Moshe Haim Shapira, I do not remember which position he held then, the Minister of Welfare or the Minister of Internal Affairs. I think that he was the Minister of Welfare at that period – Why [did this surprise me]? Because the person who this matter related to, was one of the main activists of his movement in the United States. And I saw this as more of a non-governmental activity, like the movement that was called Religious Zionism. And that it would be active in exporting children out of the country… this seemed to me – I don’t want to say serious, but it was not sympathetic indeed. I did not get an answer [from Minister Shapira]. I called and he told me “I looked at it. You know, there is a lot of gossip around this man, but he is in general a good Jew”. Somehow this relieved me a little bit. And then, I do not remember what the reason was, something ignited me again regarding this matter. That on one hand the institutions here in the country did not know about the issue, and (on the other hand) children were arriving there. I tried to interest various journalists in this story. P.8258 I must say that they took the story from me. But the story did not appear. I was friendly with the late Shalom Cohen, who was the head of the editorial office of ‘Haolam-Haze’ (This World newspaper) and in a certain conversation I told him “You know, I am sitting on a story that I think should not be silenced, that some noise should be made about it”. And then, whatever I had – and I am a bit sorry because I tried to rummage through my files and other than what I have in my head no written material is left – I gave the material to Shalom, at that time. It was agreed between us that the names should be published only in abbreviation, since nevertheless I did not know, nor do I know now, who adopted legally and who received by other means. At any rate, these were people. I have to say, that in the meantime it was clarified to me that it was not only Yemenite children, but that there were children maybe from North Africa, maybe other children. The matter was published and never received any other attention. I left it. Meaning I did what I did. I do not remember, I just remember regarding a certain incident when I was in the Yemenite Synagogue in Kiryat Ono and there, on behalf of the synagogue group, there appeared a newspaper called “Ofakim” (Horizons). And there was a person named Tov Tzadok or Tzadok Tov. Why do I remember this name? It is because the name Tov appears in the book of Ruth. I did not know whether his name was this or that way. I do not remember why, but the conversation was about this issue (of the children). Probably already then the awareness started, and probably based on the exposure they connected it to ‘Haolam-Haze’. I do not remember. But they invited me and I went. And I told them what I have been telling here now. P.8259 Beyond this I do not know. I only saw one girl. But in those circles they told me: “this one has, that one has, and that one too. Whether these were children that were not adopted legally? And so on, this I don’t know. I want to add something. At that period, when I was carrying this thing inside me, and it was a little bit, more than a little bit, I do not want to use an allegory, I do not want to say that it was like a fire in my bones, but it hurt me very much. I heard that there was a kind of inclination to say in some circles, especially religious Zionists, not necessarily extreme religious, an inclination that instead of a child being raised in a family with 12 or 10 other children, it would be better that he would be given to a family where he could live wealthy, and so forth. P.8260 There was such an inclination. This was relatively accepted here. I do not want to mention here, but if you want to mention a name, I just want to give a hint. I know that a wife of a very famous man in the country, who was a minister until a short time ago; she also claimed that she was adopted by a family in New-York. And that she got inheritance from them. Meaning, I read these things in the papers. And there are more children that were adopted by families. Whether the adoption was handled…through a court and so forth? I have to say, that this thing bothered me also for another reason. The moment the institutions, those ladies who were dealing with adoption, said that they did not know, I was bothered also from religious point of view. To say that there could be, God forbid, a question of a marriage of brother and sister, and so on. This matter bothered me a lot. But beyond what I did, I did not go for this purpose to the US and I did not appear as an investigator. This is the story. In response to a question of the chairman in the committee whether he knows how the process was done, the Rabbi answered: P.8261 I have no Idea, all I know is… and this is only what I heard from people, and you have to know that we are talking about the period of 1963-4… I think that somebody mentioned that in order to get a child it would cost $5000. Yes, it was probably the issue of flight and so forth. I have to say that this man – they called him a Rabbi. He died a few years ago, in a jail in the United States, but not about this. He was connected also with old folks homes – a very big and turbulent affair, that was going for a few years. The prosecution succeeded at the end to bring proof that old people died in the homes and it was not reported and the homes kept on getting social security for them. There were more of those kind of things. But this man was considered a respected person in the society. He would also appear here in the country. He was a member of Hapoel HaTzioni Committee and so on. His name was Rabbi Bergman, yes, Rabbi Dr. Issaschar Dov Bergman. For full testimony continue with this link.

Interview with Child Care Worker – Shulamit Malik

Shulamit Malik, 83 years old in 2017 worked in the Kadima Immigration Camp at the time of the big waves of immigration to the country. Sixty-six years later she describes what she saw in the camp while she was there. She said: - I knew that every time a group of women would come from abroad, I would have children disappearing. These were people from the camps {2nd world war survivors’ camps} who could not have babies... Link to the full interview, in Hebrew, with Shulamit Malik (published by Amram) Below is an English translation of excerpts from the interview with Shulamit Malik. The edited version appeared in an article by Tamar Kaplanski, [in Hebrew], taken from Ynet News, published on Aug 11 2017. “Whoever took him took a charming boy. With a beautiful smile and so full of life – this child was. This Zion, Zion is in my heart… I would come in the morning to work. While I would wipe my feet from the mud, he would just hear my voice, and would start to dance (shake) the bed. Hey…hey…hey… until he would reach the door with the bed. Interviewer: But Zion, they told you that he was sick?. Shulamit: Yes… sick?… not sick. No, he was not sick. He was not sick, never. There would come a group of women, 6-8 women, a group like this, they would start the visit, and I saw that they would stand beside a bed a bit longer. The next day the child (in that bed), was not there. So when I came later and I did not hear the child… Immediately it dawned on me that these delegations were not something clean [honest]. I don’t know, I simply cried. Because I understood. I started to ask, this worker, that worker… They would speak English… mainly French. They were… After, I was told that they were from Belgium. One lady, very old, came with another lady who was younger, and they were discussing, between themselves, about the children. “This one is handsome…this is not…this is such…that one is such…” They would start with the room at the end, and they would go through every room… and return again, talking again…in their French language, and… this was suspicious, what can I tell you. It was never said that they gave [the children], never. All the time I used to hear: “They took him to a hospital… the child did not feel well…go to a hospital…”… “To which hospital?”. What did these parents know? They would come back the next day to ask if the child was brought back. I felt that it was fishy, all this issue, even though I was only 18 years old. I understood that something was not clean in this business. But this was my job and that’s it, I kept quite. I got the job from ‘Hapoel Hamizrachi’. I looked for something…how can I put it?… to work… to be useful… and I started to work in Kadima [immigration camp]. Interviewer: How did they live there? Shulamit: In tents, with mud up to the knees. The beds were in water, I do not exaggerate, inside water…I thought that this was the way it was supposed to be, I did not know what was right… what was… There were many Iraqis [immigrants]. Yemenites, but less and …there were Romanians, but they were very few. In the babies’ home I did not have Romanian babies. The parents worked… Interviewer: At what? Shulamit: In corn, picking corn. I think that this woman with the girl who I have such a strong memory of, she worked in the corn (field), but probably, afterwards, she used to work in houses, probably, because she was always in a hurry… but at six [PM] she would always come back. At two she would come to nurse her, but this girl would come and would sit on the stairs in front of the entrance of the babies home. She would sit there and would nurse [her baby girl). And that day, that she came, and the girl was not there… God… what she did?… they told her that they had taken the girl to the hospital. Why hospital? They brought her [the baby] back, but she did not want to leave her there anymore. I remember once that they brought a child from home. They promised him to somebody. He was a little bit older. Just turned over a year old. They mainly were looking for baby boys, it was interesting…that the male children were taken faster. … She [the managing nurse] would come, when the child would be taken, she would come and would tell me to pack another diaper, another pair of pants, a top, underwear and a bottle with food… After I had [my own] children, I would cry sometimes, because of the pain. The past was painful. Interviewer: What hurt you? Shulamit: My heart, my heart hurt me. I would see the pictures in front of my eyes. These children. Do you know that this Zion, I can’t forget him. No chance [I would forget]. I thought that I would always have a connection with this child. I had so much love for that child. But to take him? How can one think of such a thing? “

Snapshot from the Amram video of interview

Related links

Amram – The Yemenite, Mizrahi and Balkan Children Affair

Achim Vekayamim – Facebook forum for the families of missing children

More to come…