This page looks at the relations of the Jews in Yemen with their local Yemeni neighbors prior to and during the Islamic period.

Also in the Jews of Yemen Docuweb:

Jewish Scholars

Jewish Scholars

of Yemen

________________

Kinneret and Yemenite

Kinneret and Yemenite

Pioneers

________________

Yemenite Jews &

American Colony

________________

Customs, Culture and

Customs, Culture and

Folklore

________________

Personal Stories

Personal Stories

________________

Operation 'On Wings

of Eagles'

________________

When did the Jews

When did the Jews

Arrive in Yemen?

________________

Missing Children

Affair

_______________

Relations with

Relations with

their Local Neighbors

________________

A Brief Background

A Brief Background

About Yemen

________________

Links with

Links with

Other Jewish Centers?

________________

Early Immigration

Early Immigration

________________

| Relations with their Local Neighbors

The long Jewish presence in Yemen witnessed waves of ups and downs in relations with their local neighbors. These relations varied depending on different periods, different rulers and the strength of the central regime that Yemenis were never really willing to fully accept. One way of looking at this history is to divide it roughly into two main periods – before and after the birth of Islam.

Indirect conclusions about the situation of the Jews in pre-Islamic period can be drawn from biblical texts, and from writings of a few Greek, Roman and Church historians and even from some archaeological findings. This period is not thoroughly documented. The period after the birth of Islam, however, gives us a much better picture due to documents, letters and writings from different sources.

During Pre-Islamic Period

Stone graves with Hebrew engraving on them and Jewish cemeteries found in Yemen support stories and legends claiming that Jewish life in Yemen stretches back to a few hundred years before the Common Era. It is difficult though to establish definitively what their position there was without more research.

Still we can draw conclusions, indirectly, from the bible and from later writings of Roman and Greek historians. For example, the prophet Ezekiel talked about trade with Yemen in chapter 27 ver. 19-22 where he mentions commercial ties with Sheba and Uzal (current Sanaa, the capital of Yemen). We also find a reference to Jewish activity in Yemen in Josephus Flavius’ book ‘The Ancestry of the Jews’.

Other documents have been found which suggest that there were Jewish communities in Yemen that felt safe and economically comfortable enough to support Jewish life elsewhere.

The King of Himyar Converts to Judaism

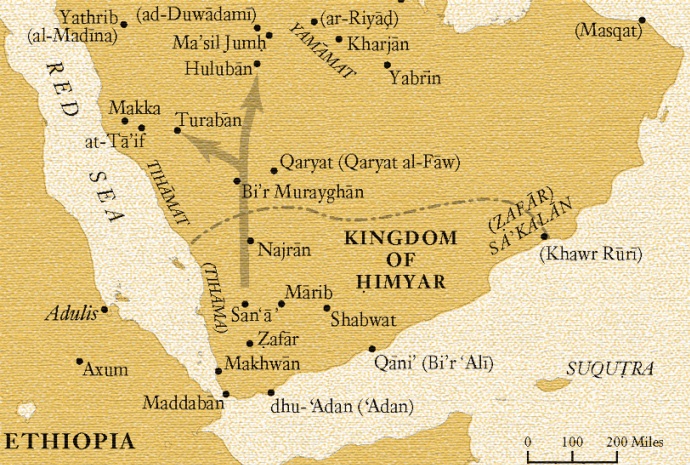

Jews that lived in the Arabian peninsula, before the Roman period, concentrated mainly in two areas – Yemen and Hejaz (today’s Northwest Saudi Arabia). During some periods, the influence of the Jews in Yemen was so great that at a certain point the ruler of the Kingdom of Ḥimyar accepted monotheism and converted, together with his subordinates, to Judaism.

The kingdom existed between ~110 BCE to ~525 CE and ruled a major territory of Yemen. The Himyarite King converted to Judaism in about 380 CE, a few dozen years after the conversion of the Ethiopian kingdom of Aksum to Christianity.

Clashes between Ethiopia and Yemen

Historically there were always conflicts between Ethiopia and Yemen since Yemen was located in a strategic point along the spice route from India and was a unique source of some of the more expensive spices.

These constant clashes were a source for wars between Ethiopia and Yemen. In addition, missionary activity by the Christian Byzantine kings, who were interested in taking control over the area, intensified the conflicts.

In a document from the mid 4th century, Church historian Philostorgius writes that the leader of the Ethiopian Empire faced a strong Jewish resistance against his missionary activity in the region.

Another interesting document that comes from church sources, can teach us about the position of Jews in Yemen and also about the connection they had with the communities in the land of Israel. Bishop Shimon of the house of Arsham, (“Eretz Kinarot” , Hirshberg, p-81) asked the Christian authorities in Israel to convince the Jews of Tiberias, then an important Jewish center, to stop helping King Yosef-Du-Nuas of Himyar (1st half of the 6th century) in his war against the Christian Kingdom of Aksum (northern Ethiopia).

One can learn about the influence of the Jewish concept of religion in Yemen from writings found in Himyar with various definitions of God, like ‘The Merciful’, ‘Lord of Heaven’, ‘Master of the Jews’, ‘God of Israel’ and so forth.

Jewish Stronghold in Hejaz

At the period of the Himyarite kingdom there was already a strong Jewish community in Hejaz. They lived in a number of villages and cities along the fertile plain, built farms, fortresses and posts. Immigrants were only able to stay there under their permission. Later they were called by Arab historians ‘The Kings of Medina’, ‘The Kings of Teima’. See Hirshberg – ‘Israel in Arabia’

As of today only legends based on the Bible, the Talmud and tradition tell us the time period of their origin. For example, of the various legends that survived, one legend tells us about the Priests that came there following the war with the Babylonians. Another legend tells about Jews that came following their defeat in the war against the Greeks.

The commerce between north and south triggered relocation of people. Arabs from the south went up north to the land of the Nabatians (current trans-Jordan), to Syria and further. Groups of Jews that fled from Israel followed the routes of the Arab and Jewish merchants and entered the Arab oases north of Hejaz. Evidence for greater waves of immigration of Jews to these areas after the fall of the 2nd temple in Jerusalem are being supported by writings and other archaeological findings. At that period, life in Arabia was free and the Jews were able to build settlements that grew and succeeded over the years.

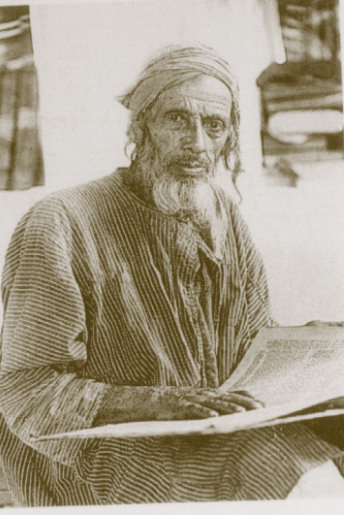

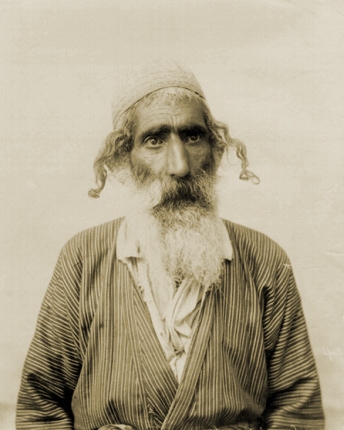

Samuel-Ben-Adaya – A Jewish Poet in Pre-Islamic Arabia

Naturally life in Arabia resulted in interactions with the local people. That meant also mutual influence. Jews learnt the Arab language, the Arab codes of behavior, their local culture, their literature and poetry. One of the important poets in the pre-Islamic period was Samuel-Ben-Adaya. He lived in the 6th century and died in Teima at about 560 CE.

Poetry was an important element in the ability to acquire social and political status at that period since it was limited to only a small section of the public. His activity as a poet enabled him to create good relations with the leaders of the Arab tribes around the area and with the governors on behalf of the Persian empire on one hand, and with those of the Byzantine empire on the other hand.

Samuel-Ben-Adaya acquired wealth that enabled him to build the fortress ‘El-Ablak’ for the safety of his family and for the inhabitants of the town in time of need. But above all he acquired respect. He was considered the ideal of honesty and justice, a man who preferred to stay loyal even at the cost of personal interests.

An Arab legend tells the story about an incident where the poet Samuel refused to hand over a deposit, given to him in trust by the Arab poet Amru-El-Keis, to the local governor who ruled on behalf of the Persians. As a result the governor killed Samuel’s son who was held in hostage. This act triggered a famous Arab saying ‘No man is loyal more than Samuel’.

Our information about the existence of the Jewish kingdom in Yemen (Himyar) comes mostly from Christian and Arab sources. A few dozen years after the collapse of this kingdom, the new religion of Islam was born. With it emerged a concept of having only one religion in Arabia. The Christians disappeared from the region. Many Himyarites were killed or gave up their religion. However, the core of the Jewish people did not convert but rather remained faithful to their belief even though they experienced suffering in the years to come.

Professor Yosef Yuval Tobi discusses the influence of Judaism on the development of Islam.

Prof. Tobi is Professor (emeritus) of medieval Hebrew poetry at the University of Haifa, Israel and Head of Ben-Shalom Center for the Study of the Jews of Yemen in Ben Zvi Institute, Jerusalem. (Duration: 2:43 min)

During Islamic Period

In Early Islam

Three strong Jewish tribes lived around the city of Yatrib (now El-Medina), in the 6th century CE: the tribe of the ‘Sons of Kinoka’ who were mainly goldsmiths, the tribe of the ‘Sons of Nadir’ and the tribe of the ‘Sons of Kuraiza’. The latter two were both mainly date growing farmers.

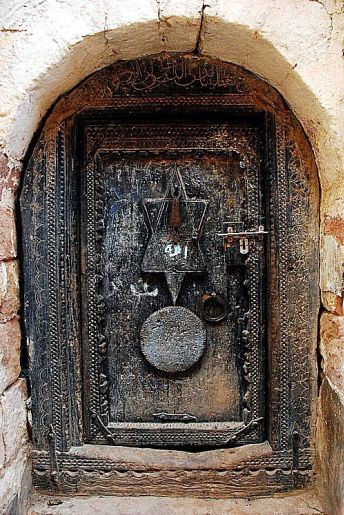

The Jewish Fortress of Khaybar

In the mid 6th century the Arab tribes Oos and Hazradj settled beside the Jewish communities around Yatrib and were influenced by monotheist motives of the Jewish religion. This fact served a few dozen years later as a solid ground for Mohammad, who fled from Mecca, to be accepted and to be able to spread his ideas among them. A short time later, many Jews were expelled from El-Medina and settled around Khaybar (Hibar).

In the early twenties of the 7th century CE the new-born religion of Islam was on the offense. The need to expand meant bringing in more followers into the religion, and fast. This was done mainly by force. While the Arab tribes joined Mohammad, accepting his ideas, at times willingly and sometimes without much resistance, the Jews, feeling superior to the new religion, were faithful to their own. They did not want to convert and rejected Mohammad’s claim of being a prophet. That meant war. Thirty Jewish leaders from Khaybar (Hibar) were ambushed and killed by Mohammad’s supporters on their way to negotiations with him.

Safiyyah – daughter of a rabbi and a wife of Mohammad

Safiyyah was the daughter of Rabbi ‘Huyayy Ibn Akhtab’, a prominent leader in the Jewish tribe ‘Sons of Nadir’. Her mother was a member of the Jewish tribe ‘Sons of Kuraiza’. The ‘Sons of Nadir’ tribe was seized in ‘Al-Qamus’, the fortress of Khaybar. Safiyyah and her family were captured. Her husband and her father, ‘Kenana ibn al-rabbi’ were killed.

Mohammad heard about her captivity and his companion suggested to him that since she was a lady from the Tribe of ‘Sons of Nadir’, which was a respected tribe, only the prophet was fit enough to marry her. Mohammad accepted his suggestion, granted her freedom and married her. She did not bear any of Mohammad’s children. Years later, she was titled, together with other wives of Muhammad, ‘Umm-ul Mu’mineen’ or ‘Mother of believers’.

“When Ali reached the Citadel of Qamus [Khaybar], he was met at the gate by Marhab, a Jewish chieftain who was well experienced in battle. Marhab called out: “Khaybar knows well that I am Marhab, whose weapon is sharp, a warrior tested. Sometimes I thrust with spear; sometimes I strike with sword, when lions advance in burning rage”

Wikipedia reference: al-Tabari (1997). The History of al-Tabari: The Victory of Islam. Albany : State University Of New York. p. 120.

Professor Yosef Yuval Tobi discusses the status of Jews under Islam. (Duration:2:27 min)

The end of the Jewish tribe of the Sons of Kuraiza

Although many other incidents regarding relations between Arabs and Jews around this period are documented, we decided to give one significant example from Muhammad’s early wars against those who resisted his authority and insisted to stay truthful to their own religious beliefs.

‘Sons of Kuraiza’ was a Jewish tribe of priests that lived in the north of the Arab peninsula. As mentioned above they lived around the Oasis where the City of Yatrib (now El-Medina) was located together with 2 other Jewish tribes. Based on tradition, Jews arrived in this area of Hejaz after the destruction of the 2nd Temple 70 CE as a result of losing the war against the Roman Empire that conquered Jerusalem. The Jews brought with them organized and systematic agriculture which gave them a clear advantage over others in terms of culture, economics and local politics.

In the 5th century CE two tribes from Yemen arrived in the area. Conflicts between the different tribes triggered political agreements and alliances. In 622 Muhammad and his followers arrived in the region, finding a fertile ground of followers who were already influenced by the monotheistic aspects of the Jewish religion around them, and received the principals of the new rising religion. In the year 627 CE. Muhammad’s forces, led by the Kureish tribe that he originated from, attacked Yathrib. The Kuraiza Jewish tribe tried to negotiate. After unsuccessful negotiation the tribe had to surrender. A few of the men converted to Islam and were saved. The majority, a few hundred men, were beheaded under the supervision of Mohammad. The wives and the children were captured, forced to convert to Islam and were sold for slavery.

The Jizyah Tax

Within a few dozens of years the new religion stormed over the Arab peninsula and then expanded north including Asia Minor, North Africa and Spain in Europe.

At a certain point Damascus in Syria became the center of the new Empire. The Empire was divided into provinces that dealt each with the administration of its own. The governor of each province was appointed by the Caliph in Damascus and was obligated to send tax money to the central control located in Damascus. In general, non Muslim monotheistic religious minorities like Jews and Christians had to pay an annual tax per capita for protection, known as Jizyah.

The concept of the Jizyah was first introduced in the Koran (the Islamic Religion’s holy book). In verse 9:29 it says (Sahih International English Translation):

Fight those who do not believe in Allah or in the Last Day and who do not consider unlawful what Allah and His Messenger have made unlawful and who do not adopt the religion of truth from those who were given the Scripture – [fight] until they give the jizyah willingly while they are humbled.

The above gave the authorized stamp to enforce Islam decisively among pagans. For Jews and Christians, however, this order was replaced with a tax that let them keep their own religious beliefs but left them as lower-class citizens.

This practice was actualized sometimes using severe measures and sometimes in softer forms throughout the centuries, all depending on the waves of extremism, the level of control of the central regime and the approach of the local rulers in the Islamic countries and within it Yemen.

During the Islamic Golden Age

Expand to read about 'What is the Islamic Golden Age?' .... The 19th century term Islamic Golden Age refers traditionally to the period from the 8th to the 13th century, ending with the invasions of the Mongols. Some scholars today, however, extend the definition of this period to include the 15th and 16th centuries. The Islamic Golden Age started with rule of the more tolerant and open Caliph Harun al-Rashid (786 to 809) of the Abasid Caliphate. It was characterized by the development of language and culture in Islam, by rich literature and by the flourishing of sciences. During this period the Greek, Roman, Persian and Aramaic mythologies were translated into Arabic and areas in sciences were taken to higher levels of research and development.

The attitude to non Muslims during the Islamic Golden Age loosened. Although Jewish and Christian subordinates experienced somewhat easier lives then, they were still defined as 2nd class citizens. They continued to pay the yearly tax for protection (the Jizyah) and, together with some other decrees, this kept them at a lower status. The decrees that were enforced regarding the non-Muslims were listed in the Pact of Umar”.

Expand to read about 'What is the Pact of Umar?'.... The Pact contains sets of rules, laws and regulations written during the 7th – 8th to establish relations of non Muslims under Islam. Although there is some dispute among scholars regarding the origin of the Pact of Umar, the general agreement is that it was originated either in the 7th century by the Rashidun Caliph Umar ibn Khattab or during in the 8th century by the Umayyad Caliph Umar II. Also there are some different versions of the Pact that can indicate changes and nuances that were made throughout the years. The bottom line is that it was a set of rules, laws and regulations that were written in order to formulate the status of non Muslims that live under Islamic regime. Below there is a list of rules that exist in various versions of the Pact. (From Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pact_of_Umar).

This tax was abolished only in the 19th century by the Turkish Sultan Omar.

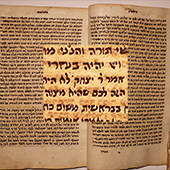

From the 8th century, for a substantial period, most of the Jews were under an Islamic regime. A large number of them spoke Arabic and the connection to the other Jewish communities, in areas occupied by Islam, became much easier than before.

The Jewish religious authority at this period was located in what is today Iraq (Bagdad). It was respected by the Jewish communities and it had a great influence over them regarding life and religious thoughts. The spread of the ‘Babylon Talmud’ among these communities is one example of this influence.

In different periods, when life in certain areas were more oppressive, some Jews who could afford it moved to another country under the rule of Islam. One example for this phenomenon was the relocation of Maimonides from Spain to Egypt.

The term Dar-el-Islam (The House of Islam) is the principal defining that wherever there are Muslim majorities, the rules of Islam should be exercised. The term was already established in the Arab peninsula, and in some other parts of the Middle-East, as early as the 8th century CE. When the term first appeared, it was meant to define the areas where Muslims could safely practice their religion. In the centuries to come its meaning was extended to justify an aggressive approach used by extreme Islamic groups against secular-based societies with Muslim majority, to enforce the laws of Islam.

The experience of the Jews with their neighbors in Yemen during the Muslim rule changed depending on the approach of different rulers at different times. As a result they could not enjoy a continuous calm and quiet life. In 1165 CE for example, King Abed-El-Nabi demanded from the Jews of Yemen to convert to Islam or to face death. Many Jews chose life; they packed a praying rug and rushed to the mosque. Many of them, who lived during that time, were split between the two religions. They were practicing Judaism secretly at home until the dark period would clear, as did their brothers in Portugal, a few hundreds of years later.

1st Ottoman rule in Yemen 1546-1629

During the 1st Ottoman period in Yemen, the pressure on the Jews was somewhat relieved and their lives improved. It was easier for Jews to move from one place to another.

This relative comfort continued until the Quasam dynasty in Yemen took over in 1629. From that time, and for the next 200 years, the conditions of Jewish life deteriorated, new rules limited their activities and they were forced to observe restrictions of different kinds such as the prohibition against headdresses as an act of humiliation. This act was called the ‘decree of crown’.

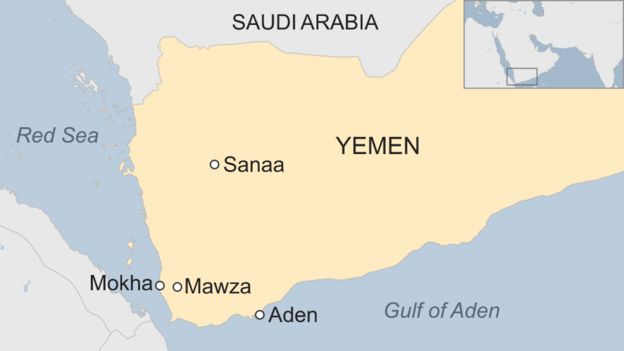

Mawza Expulsion (1679)

The expulsion to Mawza that occurred in 1679 CE was the strongest and the most significant event that affected the Jews of Yemen ever. In 1676 Yemen was ruled by Imam Ahmed ibn Hasan ibn Al-imam el-Kasam, known as Almahadi. When he took over, Yemen was divided into about 10 smaller entities. In order to strengthen his regime he wanted to unite them all and claimed that Yemen is holy to the Muslims and cannot contain another religion in its territory.

Orders regarding the Jews

At first he ordered the Jews to close their synagogues and forbid public gathering for religious activities. Jews were forced to pray individually at their homes. Then he requested that all Jews should convert to Islam following the order of the Caliph Omar which stated that only one religion was allowed in the Hejaz. Most of the Jews at that period refused the conversion. In 1679 the Imam ordered the expulsion of all the Jews from all territories of Yemen to the hot arid climate land of the Tahima along the Red Sea and not far from the city of Mawza.

Being faithful to their religion and keeping their united entity intact, the leaders of the communities sent messengers to all cities and villages where Jews settled and organized them. Family leaders gathered their own members, joined convoys that were formed and started the long tough journey to the unknown.

The expulsion order covered all parts of Yemen from Hyidan and Tzaada in the north to Sharab and Aden in the south. The claim that their Judaism goes back to the time of Muhammad, and even before, did not help them.

Jewish efforts to unify and elevate the community

Detailed information about the expulsion can be found in poetry and prayers which describe the suffering that they experienced. They describe the sudden removal of the Jews from their homes and villages and the destruction of the synagogues.

The elders tried to uplift their spirits and help them to go through the first shock. In a few cases, especially in some villages where there was insufficient religious and spiritual support, some broke and converted to Islam.

Due to the mountainous topography of Yemen the expulsion took place at different times, starting in Sana’a. On their way passing through cities and villages that were populated by Jews who had not yet started their move, the deportees received accommodation, water, foods and other support. The most generous, as described by some of the poets, were the Jews of Dahaban, Kohvan, Arus and Altvila.

Conditions under the Expulsion

The extreme weather conditions – heat during the day, cold during the night, thirst, hunger, illnesses and robbers took their toll. Thousands died or were killed by the time they arrived at their destination. In Mawza itself, there were only a few water wells and they were mostly salty. The Mayor of Mawza was prepared in advanced by Rabbi Saliman El-Nakash, the leader of the Jews of Sana’a, regarding the waves of expelled Jews that were coming. To his credit, Said Ahsan, the Mayor, welcomed them as they arrived, with water and bread following the custom of hospitality in the Arab world.

Except that this spark of light did not change the bottom-line results. Individuals and whole families lost their lives and only about a third of the Jews survived. Out of the community of 10000 from Sana’a, for example, only 1000 endured.

Loss of books and documents

The expulsion to Mawza not only cost in terms of lives and property, it also had an impact on the culture, literature and history of the Jews of Yemen.

Thousands of valuable books, poetry, community documents disappeared, burnt, were stolen or damaged with no option to mend or replace them. Although the Jews of Sana’a left a number of those books in the city with non-Jewish neighbors for safety, they discovered on their return that all were burnt to ashes.

The expulsion was a disaster for the Jewish communities of Yemen but it did not do any good for the Muslims either. The Jews, who mostly did not own land in Yemen, made their living by providing services to the Muslims. They held the occupations that every society cannot do without. They were the builders, the blacksmiths, the goldsmiths, the shoemakers, the merchants and much more. About a year after the expulsion, the Yemenite leaders throughout the regions of Yemen started a campaign against the Imam demanding to bring the Jews back. Floods in the Amran zone that destroyed houses and fields in the region triggered its governor to initiate the request since he needed the expertise of the Jews to overcome the crisis. As the other rulers joined him for the same need, the Imam agreed and gave an order to do so, as long as Jews do not return to their original homes.

Return and start from the beginning

One example of many for this restricted order of return relates to the Jews of Sana’a. Instead of resettling in their original neighborhood in the city, they were forced to build a new suburb in a valley that was called Ka-el-sama (valley of the hyena), this was renamed from that point on to Ka-El-Yahud (valley of the Jews).

The Orphan Decree

The orphan decree was based on a word-to-mouth tradition in the Muslim world that every man is born under the natural religion, Islam. According to this tradition, parents are those who make their children believe in another religion like Judaism or Christianity. Therefore if a child’s parents die, it is imperative to bring him/her back to the natural religion.

Throughout the centuries leaders and rabbis of the Jewish communities risked their lives trying to keep the Jewish orphans within the Jewish communities. They smuggled them from place to place, removing them from the centers and relocating them in small distant villages, hiding and feeding them until they grew up, and marrying them young.

From the early 20th century, they smuggled them to Aden which was a British colony then. The children at that time were sent to Israel, which was under a British mandate after the 1st world war.

The Jews who were involved in this activity suffered a great deal. They were arrested, tortured, and in some cases were forced to convert to Islam.

This decree was enforced in different degrees throughout the centuries. During the period of Imam El-Mantzur Ali of Sana’a (1776-1809), known to be lecherous and lusty, Jewish orphans were caught in the city, converted to Islam and were forced to serve in his palace.

Some Examples of Jewish Economic Activity in Yemen in the 19th Century

The following provides a small sample of economic activities of Jews in Yemen during the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Mocha, Aden and areas in Yemen under the Turks.

Mocha

As a result of Mawza expulsion in 1679 and due to the political unrest in Yemen, Jews in the country experienced economic and social difficulties for a few dozens years. From approximately the 1730’s, under the leadership of Rabbi Shalom Araki, their lives changed substantially. Some of the Jews gradually took a part in the growing international commerce with India and with other countries. These merchants were primarily from Mocha and Sana’a. Some of them emigrated to India and settled along the west cost of the country. mainly in Cochin, Bombay and Calcutta.

Yaakov Sapir, following his tour in Yemen in 1864, wrote in his book ‘Even Sapir’ about the Jewish community of Mocha that was located by the shore of the Red Sea:

“…there were 400 Jewish families, and they were rich, merchants and experts in various occupations. This town, was a major commerce center for all cities in the Kingdom of Yemen from the sea and from the land…”.

As mentioned in other pages of this project, Yemen, due to its location, has always been a subject of political interests that triggered wars in the area. The development of technology and transportation even intensified the process. During the 19th century England, Turkey, Egypt and to some extent Portugal were involved.

In the early 19th century the importance of Mocha diminished. Two other cities replaced it. These were Hudaydah (on the shore of the Red Sea) and Aden in the south of Yemen on the shore of the Indian Ocean.

The Egyptian leader at that time, Ibrahim Pasha, took over the Tihamah along the shores of the Red Sea. He practically destroyed Mocha. Most of the Jews escaped the city to the towns inland. Some of them settled in Aden.

Aden

The city of Aden was conquered by England in 1839. Soon afterwards it developed into an important connection and commerce center. The Jews took part in its development. Many of them served in the city under the British administration and were exposed to the changes and new opportunities that this offered. They learned more about the western culture and as a result also about customs and traditions of Jewish communities elsewhere.

The equal rights, granted to them by the new rulers, served them well. Many of them succeeded in their economic activities. They supplied goods to the British Army, which was stationed in Aden, and helped to develop the city’s import/export activities .

The victory of the Turks in Yemen in 1872 practically divided the country into two entities. The south was held by England, the north by the Turks. In the years to come this roughly determined the line between the two temporary states of North and South Yemen, which eventually merged back into one state during the 60’s of the 20th century.

Turkish areas in Yemen

The economic activity during the Turkish period in Yemen grew due to greater population and the need for supplies to its army. In general the Turks had a somewhat softer approach towards the Jews than the earlier Yemeni regime.

The Turks realized that the Jews could serve as an important factor in the development of the economy because they were the craftsmen while the Arabs were mainly the farmers and the land owners. In terms of commerce, also, Jews who fled Mocha to the cities inside Yemen had some advantage over the local population due to their experience and connections. They succeeded in their export/import activities across the Turkish ruled territories and one could see them in many cities like in Sana’a, Yarim, Taez, Dhamar, Amran and more.

Constraints over the Jewish economic activity were enforced after 1911 when the Imam Yahya, who was appointed by the Turks, decided to have a tighter control over his territory.

He activated specific measures that would eliminate their economic achievements which were gained earlier. Some claim, like professor Yosef Tobi, that perhaps this activity was not targeted intentionally against the Jews. This may have been a result of his policy to have, under his personal control, the economic resources of the country in order to eliminate accumulation of capital among its citizens in order to avoid any chance of rebellion.