Early waves of ‘group’ immigration from Yemen arrived in the land of Israel already in the 2nd half of the 19th century. It should be noted, however, that small groups and individuals came and left even earlier throughout the centuries.

Also in the Jews of Yemen Docuweb:

A Brief Background

A Brief Background

About Yemen

________________

Early Immigration

Early Immigration

________________

Links with

Links with

Other Jewish Centers?

________________

Operation 'On Wings

of Eagles'

________________

When did the Jews

When did the Jews

Arrive in Yemen?

________________

Relations with

Relations with

their Local Neighbors

________________

Jewish Scholars

Jewish Scholars

of Yemen

________________

Missing Children

Affair

_______________

Kinneret and Yemenite

Kinneret and Yemenite

Pioneers

________________

Personal Stories

Personal Stories

________________

Customs, Culture and

Customs, Culture and

Folklore

________________

Yemenite Jews &

American Colony

________________

| Early Immigration

More content for this page is coming soon

Multiple waves of immigration from Yemen spanned the years from the end of the 19th century up until the operation of ‘On Wings of Eagles’ (1949 – 51).

What triggered the immigration of Yemenite Jews in 1881-2

A few answers can satisfy the above question.

A belief in the biblical prophecy of the return to Zion became a realistic vision after the Ottoman conquest of Yemen in 1872. At that point the Ottoman Empire held both Yemen and the land of Israel. This enabled residents of Yemen to move between the two areas with greater ease.

The British acquisition of Aden from 1839 and the Ottoman conquest of Yemen in 1872 accelerated the development of communication, transportation and a shift in economics. Products of the industrial revolution became available, pushing traditional occupations aside. This had a substantial impact on the Jewish population who were, to a large extent, craftsmen.

Unrest among the tribes that rejected the Ottoman rule affected the Jews and influenced their decision for relocation.

Messages about the growing population in Jerusalem triggered their imagination for deliverance and their desire to take part in the process.

Also, some scholars would even mention the rumors about Laurence Oliphant’s plan (1879) for purchasing land in the east and west bank of the Jordan River – a plan that may have been one of the triggers.

Background – Life in the Holy Land in the 19th Century

Dependency on Philanthropy

Most of the population in the land of Israel, until the end of the 19th century, relied on philanthropy for their living. The residents at that time believed they were entitled to this support from their brothers around the world since they lived in the holy land, they studied Torah, and they prayed for the children of Israel wherever they were. They also believed that their actions would bring deliverance for the people of Israel, faster.

The mechanism of fund raising was improved during the Ottoman period. Expand to read more... Many emissaries were sent from the communities in Jerusalem,

Tzfat, Hebron, Tiberias and more, to the Jewish

communities around the world for the purpose of supporting the Jews in the land of Israel. Some were sent as far as the USA, Australia

and Central Asia. These funds were used to

support orphanages, schools, charity projects, building new neighborhoods

outside the walls of Jerusalem

and for the purchase of land. Between the Sephardic and the Ashkenazi administrations there were differences regarding the way the funds were divided. The Sephardic community gave the money to the leaders and to the scholars. The Ashkenazi community would divide it based on the number of members in the family with the approach that one third would go to the needy, another third would go to scholars and the last third would go to public institutions.

Dominance of the Sephardic Community during the 19th Century

For a few hundred years, the Sephardic community in the land of Israel was mainly made up of the descendants of expelled Spanish Jews (from 1492) and the Jewish descendants from the Muslim countries.

Under an order from 1841, the chief Sephardic rabbi (called ‘Haham Bashi’) was recognized by the Ottomans as the top authority in all matters of the Jewish communities... Expand to read more... He was its official representative and his position was equal to that of the chiefs of the different Christian communities Other groups of Jews from Islamic countries were not recognized

as separate organizational units, but were classified under the hegemony of the Sephardic community. From the mid 19th century, requests by the different communities

for organizational independence were made. Some of these communities achieved

their goal already by 1914. The reason for the demand for organizational independence was

mainly economic. One of the claims was that the distribution of resources among the different communities was not proportional to the level of support that was given by the Jewish communities in the countries they came from.

The Yemenite Jews make their claims

The Yemenite Jews, during the early years of arrival, mostly lived under poor conditions. The needy ones received minimum support.

They claimed that the Sephardic leaders were responsible for their situation. Expand to read more... They claimed that, in spite of the ongoing support that the Sephardic administration received for them from Yemen, they did not receive a comparable amount of help, as promised by the Sephardic administration. The Yemenite Jews also complained about the high taxes they had

to pay. They also rejected the attempt of the Sephardic administration to

change their traditions within the family. Another issue was the Ascaria tax (exempting

them from being recruited to the Army). In 1891, not being able to pay it resulted

in the arrest of some respected members in the community. This tax was paid to the Ottomans by the Sephardic

administration. It claimed, at a certain point, that there were other needier groups

to support. They claimed that the Yemenite Jews improved their economic status

and should be able to pay the tax. A representative of the Yemenite community, Rabbi Avraham

Elnadaf, was sent to Yemen

to raise more funds for the Yemenite Jews. This generated anger by the

Sephardic administration, which reacted with a strong letter to the leaders of

the Yemenite community in Sana’a. Throughout the years, conflicts between the Yemenites and the

Sephardic administration existed at different levels. An appeal to the “Haham

Bashi” in Turkey,

forced the Yemenite community to continue to be under the Sephardic hegemony. It is only with the revolution of the “Young Turks” in 1908, that the Yemenite Jews were able to separate themselves from the Sephardic control. They established independent institutions for education,

religion, social matters and even a community court. In order to finance the

public activity, taxes were established and support was received from the rich

members of the community. Representatives of the community were also sent to raise

funds. They went to Europe and to other places like Bukhara, where a relatively affluent Jewish

community lived. It should be noted though, that not all members of the Yemenite

community were in favor of the separation. A minority, which followed Mori

Yihye Tzarum, remained loyal to the Sephardic Kolel. The Jewish Yemenite community faced financial crises during the

1st WW. Its public services could not function without ongoing support. The

conquest of the country by the British army sped up the recovery.

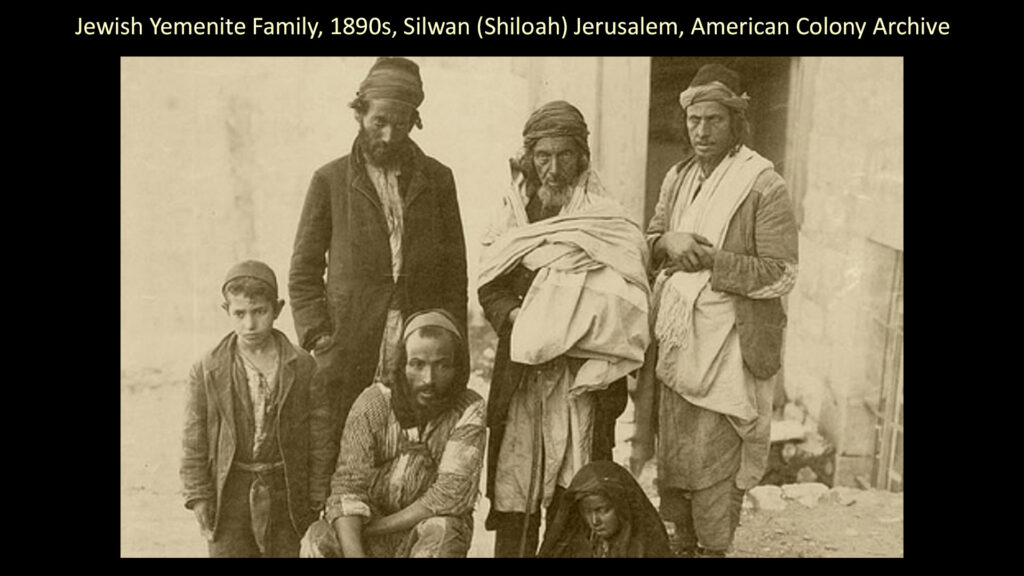

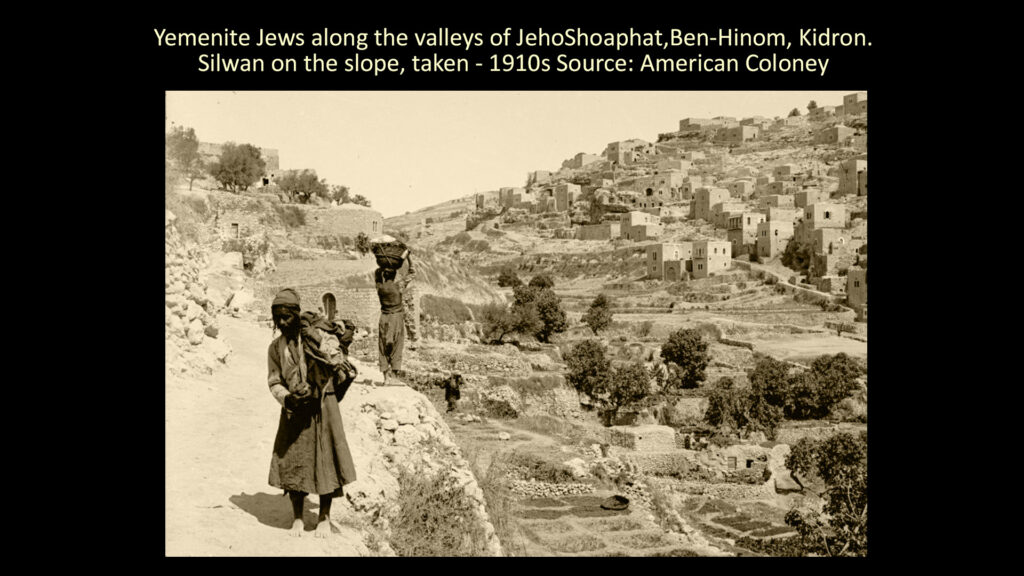

Silwan on the slope, taken – 1910s Source: American Colony

Immigration of 1881 – 1882

In the summer of 1881 a few families from Sana’a picked up their goods and started the long journey to the promised land. They left Sana’a in August and arrived to Hodeidah, on the shore of the Red Sea, crossed to Massawa in Eritrea and arrived to their destination through the Suez Canal.

The families of Rabbi Shalom Nakash and the family of Yosef ben Shlomo Nadaf were the first ones. Two months later in Oct 1881 the families of Rabbi Aharon Araki and Rabbi Avraham Alsheich followed them.

Optimistic letters sent to Yemen by the new arrivals triggered another wave of about 150 Jews who left Yemen in August 1882. Out of this group only a few dozen arrived to Jerusalem, due to a difficult journey plagued by health and climate issues, often resulting in death.

The majority of the new immigrants during this period arrived to Jerusalem. Few of them stayed in Jaffa, where they landed.

First steps in Jerusalem

The first group arrived in Jerusalem in September 1881. A second group of a few dozen people arrived in April 1882. A third group arrived 4 months later. The groups consisted of young families and singles who did not belong to any form of organization.

These groups arrived as a result of spiritual and religious aspirations. They experienced a harsh reality upon their arrival due to lack of cash, work and social support. The suspicious reaction from the existing organized Sephardic and Ashkenazi populations, made the Yemenite Jews’ integration even more difficult. Yet, it did not take long before they realized that the newcomers, who were different in look, language, dress and behavior, were actually their own people who needed immediate support.

Indeed, food supplies and temporary shelters were arranged. But still, support was limited because the leaders of these communities felt a stronger responsibility towards their own members.

Lack of work

Most of the Yemenite Jews who came during these waves were from the highlands of central Yemen where, as a whole, farming was out of range for them. They supplied their local Arab neighbors with services primarily as shoemakers, cobblers, blacksmiths, silversmiths, goldsmiths or merchants.

The size of the population in Jerusalem when they came did not support an overflow of these occupations. Moreover, some of these professions needed an initial capital to start with, something that they were missing, since most of the money they left with was used up during the months of their difficult journey from Yemen.

The American Colony and the Jews of Yemen

The limited support from the existing Jewish communities was not enough to supply the basic needs of the recent immigrants from Yemen. A short time after their arrival to Jerusalem they received help from an unexpected source. Members of the American Colony decided to help a number of families with food, supplies and accommodations.

The following is a quote from “Our Jerusalem – An American Family in the Holy City, 1881-1949” by Bertha Spafford:

“….One afternoon in May 1882 several of the Group, including my parents, went for a walk, and were attracted by a strange-looking company of people camping in the fields. The weather was hot, and they had made shelters from the sun out of odds and ends of cloth, sacking, and bits of matting. Father made inquiries through the help of an interpreter and found that they were Yemenite Jews recently arrived from Arabia…”

Read about the American Colony and the Yemenite Jews in https://wysinfo.com/the-jews-of-yemen-the-american-colony-and-yemenite-jews-in-jerusalem/

Israel Dov Promkin and the Yemenite Jews

During the 2nd half of the 19th century, Jerusalem was a poor and somewhat alienated city. Israel Dov Promkin was the publisher of the magazine “Havatzelet” at the time that the first waves of Yemenite Jews arrived. He saw the disheartening condition they were in, and was aware of the responsibility he had, as a Jew, to act to improve their situation.

Promkin published a few strong articles that described their conditions, calling the Jewish communities in the country and abroad to help their own people.

He, with others in the Jewish administration, established a group called “Ezrat Nidachim” (Help for the Needy) in honor of Sir Moses Montefiore, and raised money to build housing for the new immigrants. Promkin stood beside the Jewish Yemenite community in Jerusalem and helped them until they were able to set themselves up and support themselves.

First neighborhoods outside of the walls

The growing need for accommodations generated a local initiative by “Esrat Nidachim” and other Jewish organizations like “Keren Moshe fund’, to build outside the walls.

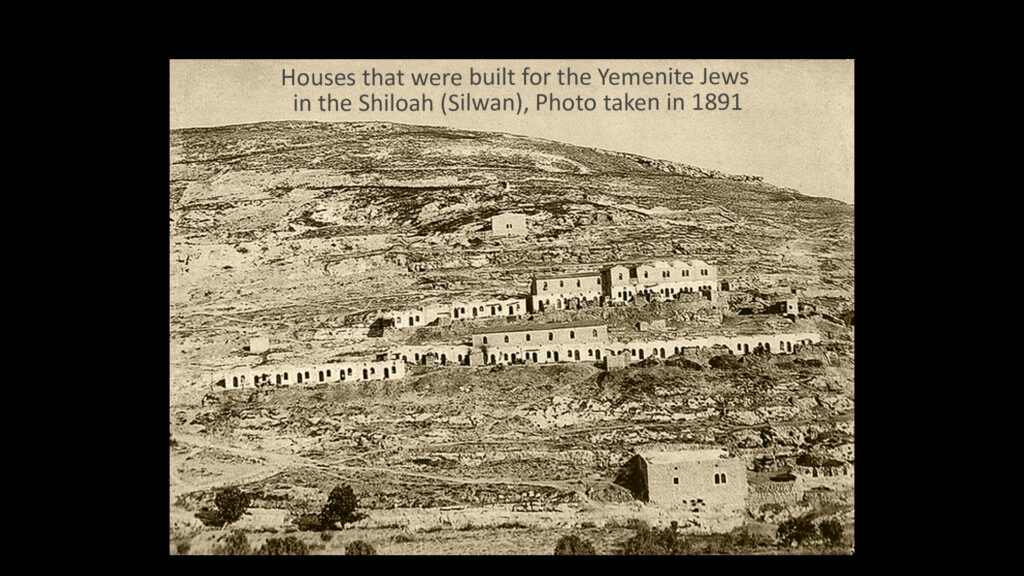

Silwan (Kfar Hashiloah)

As a result of a shortage of housing inside the city, some of the Jewish Yemenite families chose to move outside of the walls. They found caves in the western slope of the Mount of Olives close to the small Arab village of Silwan. They cleaned and prepared the caves for living.

Promkin’s call to help the new immigrants had a response. A plot of land in Silwan was contributed by Boaz ben Yehonatan Mizrachi. Money for building was contributed by an affluent Jew from London, Kalman Volraich and others. Soon after, enough money was collected to build the first houses.

In 1884-5 three houses were completed. A year later, twelve houses were ready for use. By 1888, twenty five houses were already finished and occupied. Since the number of the families was still greater than the houses available, a lottery was made. This granted the winners the right to stay in the house they won for 3 years. Then they had to pass it on to the next family that was waiting.

In 1891 the “Ezrat Nidachim” organization was able to complete 65 houses, synagogues and a school. Throughout the first few years most of the residents in Kfar Hashiloah were Yemenite Jews.

In fact, Kfar Hashiloah was the biggest neighborhood of Yemenite residents in Jerusalem outside the walls. In its prime it contained a few hundred Yemenite Jews.

Due to the relative distance from the city center they were able to form a crystallized society. Their leaders, in general were close to the Sephardic administration but kept their traditions from Yemen, minimizing the influence of other Jewish communities who lived within the walls. Most of the Jewish Yemenite members who lived in the city were inclined to form an independent organization that would be responsible for their own affairs.

In general, relations with the Arab neighbors were reasonable, but deteriorated gradually with the rising Arab nationalism.

Mishkenot

One of the neighborhoods was ‘Mishkenot’, which contained 13 houses (actually extended rooms) that were dedicated (assigned) for the Yemenite Jews. The buildings were built within the existing ‘Mishkenot Israel’ area, to serve as temporary homes for Yemenite families.

The idea was to help the families during the first period in the country, hoping to ease the process of adjustment, and to help them to reach a level of independence more quickly.

In order to give the needy an even chance for progress, and due to the shortage of housing, it was decided that the families that were granted the rights to live in the houses would be replaced every 2 years by other families. One of the thirteen houses served as a synagogue that was later called “Synagogue Hagoral” (the Synagogue of the Lottery).

Creating the neighborhoods in Kfar Hashiloah and in Mishkenot did not solve the problem of housing for the Yemenite Jews in Jerusalem. Many families still lived in difficult conditions and in temporary rentals, unlike in Yemen where even the poor had a house of their own.

Nahalat Tzvi

In 1892, Nahalat Tzvi, was created. In 1889, after saving an amount of money, some 30 families gathered with the intention to build a neighborhood for themselves. They bought a piece of land and, with the help of the Baron Hirsh together with “all Israel Friends” association, in 1892 they built the first 17 houses near the Mea She’arim neighborhood. It was called Nahalat Tzvi in honor of Baron Tzvi Hirsh.

In the years to come the neighborhood became a center for the Jewish Yemenite community due to the number of synagogues that were there and since many of the rabbis of the community lived there.

More small neighborhoods were built to serve the Jewish Yemenite community. For example, Shaarei-Pina (the Gate of the Corner) built in 1889, ‘Shabbat Tzedek’ and ‘Beit Salem’. Also ‘Nahalat Shimon’, built in honor of the great priest Shimon Hatzadik from the 2nd Temple period, whose grave is located close by.

Nebi Samuel

In the mid 1880s there was an attempt to create an agricultural village in Nebi Samuel. Yaakov Mann, who owned some 3500 dunam of land, designated it originally for European Jews (of Poland). In 1886 “the committee of the village ‘Nahalat Israel Rama’” was formed for this purpose. Poor response to join the project killed the original thought, and after a few years there was still no success.

Some time later Promkin, the man who took upon himself to help the Yemenite Jews, suggested offering the land to them. Whoever had the money paid for his lot, while the others were able to purchase it with his help. In 1895, thirteen families held 600 dunam of the land. Initial help allowed them to prepare it for agriculture. They grew wheat and planted wine groves on some 150 dunam.

The new farmers stayed in the fields throughout the week and slept in caves and huts. On Shabbat they went back to their families. Often, when the new farmers returned to the fields to start the new week of work, they would find that the plants and the products in the fields were sabotaged.

The relations between the Jewish Yemenite group and neighboring Arabs deteriorated. The acting committee of “Hovevei Tzion” refused to help the group since it had heavy obligations to support the settlements in ‘Mishmar Hayarden” in the north of the country.

As a result of the conflict with the Arabs and a lack of support by the administration, the Yemenite farmers abandoned the land. At this point, the Turkish authorities decided the land was disputed territory and would not let them come back.

Life of the Yemenite Jews in Jerusalem improved slowly due to organizations like ‘Kol Israel Haverim’ and ‘Ezrat Nidachim’. These organizations were supported by rich Jews, like the Baron Hirsh, Nissim Bachar and others. The help included training in needed occupations, loans for housing, and teaching the codes of behaviors in the new environment. In some cases their training or jobs were conditioned by an obligation to save a certain percentage of their salary for future use. . By 1887 there were about 443 Yemenite Jews in Jerusalem. With time, the Yemenite Jews began to organize themselves like the other communities in the city

Silver/Goldsmiths in Ben Shemen

Ben Shemen, located half way between Jerusalem and Jaffa, was a training agricultural village built by the Palestine Office. There was an attempt to introduce a project for the new immigrants that would combine agricultural work and fine industry.

In 1910, the Palestinian office sent about 10 families of silver/goldsmiths from Jerusalem to the village. The purpose was setting up a factory and keeping the families active in their proffesion. The art products manufactured would be sold to Betzalel (the School of Art). Also each family would receive a parcel of land to grow whatever was needed for living.

Obstacles appeared already at the beginning. What was promised to the families was far beyond what was possible to provide. A few months after arrival, the group was requested to pay rent for the houses supplied to the families. The group of goldsmiths said that they were willing to pay towards buying the houses but not willing to to pay rent, which would be a loss for them.

On top of that, the group suffered from a lack of water. Very often they had to bring it with buckets and carry them with donkeys.

The relationships with some of their managers deteriorated. The Jewish Yemenite group complained to Professor Shatz, the director of the Betzalel art school, and to the Palestine office. Detailed letters from the group did not change the situation. They were suspected of “not being reliable”. The Betzalel school management threatened them, saying it would cease their employment and would not pay their salaries.

The families that needed the anchor of continuous work kept on for some period. At a certain point they had to leave the place. Some were laid off, others moved back to Jerusalem. The three-year experiment ended in failure.

Eventually many of these craftsmen became well respected in Betzalel.

What triggered Yemenite Jews to come in 1912 – 1914

In addition to the longing for a return to the land of Israel, the Jews of Yemen responded to a practical need for a working force that would supply the demands of a rapidly growing population.

After Herzl’s death, during the 7th Zionist Congress in 1905, there was a shift from political Zionism to a more practical approach. They established the Palestine office which focused on promoting and developing agricultural settlement and industry in the country. There was a need for a working force. The idea was raised to send an agent to Yemen in order to bring Jews who, they thought, could do the agricultural work that was traditionally done by the Arabs.

Amatzia Levy Hevrony, an educator, gives the background of this period in pre-state Israel. He provides the main reason for a wave of immigration generated between 1912-1914, where a few thousand Jews picked themselves up, leaving their goods, and started their long journey to the promised land. (duration 10:07 Min.)

Amatzia Levi-Hevrony describes Shmuel Yavnieli’s Mission to Yemen in 1910-1911 to stimulate the Jews of Yemen to immigrate to pre-state Israel. See https://wysinfo.com/the-jews-of-yemen-front-page/ for more about the Jews of Yemen. (Duration 13:20 Min.)

Amatzia Levi-Hevrony describes the first steps of the Jewish Yemenites in Zichron Yaakov. See https://wysinfo.com/the-jews-of-yemen-front-page/ for more about the Jews of Yemen. (Duration 19:08 Min.)

Yemenite Jews living in Zichron-Yaakov wrote in 1925 a strong letter to the Baron Rothschild representative in Palestine (pre-state Israel). They wanted, like others, to be farmers who cultivate their own land, and not the ‘element’ that would work for the others…. See https://wysinfo.com/the-jews-of-yemen-front-page/ for more about the Jews of Yemen. (Duration 4:14 Min.)

The Jewish Yemenite Union in Israel

The Yemenite Jews found it difficult to integrate into the administrative establishment. Their relations with the “Histadrut”, the general organization of workers created in 1920, were not good.

They had difficulties being accepted into the agricultural settlements and within the existing society in the country from the time they arrived.

There were different reasons for these difficulties. Some were due to social/cultural differences, some were due to a different political approach and others due to organizational structures.

The Yemenite Jews requested the intervention of the Histadrut in their conflict with the administration responsible for agricultural settlement. They wanted to be treated equally. The Histadrut would not intervene.

In 1923, forty two years after the first group arrived to the country, the Yemenite community established a union. They set up an organization called ‘Hitahadut Hatemanim Be-Israel’ (The Union/organization of Yemenite Jews in Israel). Its aim was to take care of their economic, political, and cultural interests.

Finances for the activities of the Union were raised from the members of the community and from Jewish communities in North America. The establishment in the country did not appreciate the competition over fund raising from the Jews abroad, and took actions against it.

Throughout its 28 years of activity the Union helped Jews to leave Yemen for Israel and was involved with their absorption into the country.

At the time the Union was established, Yemenite Jews were already spread across the country. They lived in Rishon Letzion, Petah-Tikvah, Rehovot, Zichron Yaakov, Hadera, and more. The Union took upon itself efforts to extend the settlement of the community members and triggered settling in Hertzelia, Pardesia Netanya etc.

The union was involved in the efforts to help the Jewish Yemenites of Kinneret, after they were forced out of their homes, to relocate to Marmorek beside Rehovot.

Important activity – First agricultural Village

Perhaps one of the more important activities, maybe not because of its size but because of the precedence, was the establishment El-Yashiv in 1933. It was the first agricultural village for the Jews of Yemen.

El-Yashiv was established after stubborn relentless struggles by the union.

It marked, one could say, a beginning of a shift from the original approach of the establishment. Yemenite Jews were now working on their own farms in the country and not merely as hired agricultural workers.

Criticism from within the community

Yaakov Gluska was born in Yemen in 1900-1 and arrived in the country in 1908 with his parents and family members. He experienced, like many others during the early 20th century, periods of difficulty and hardship but, with time, was able to reach a level where he could assist others.

Yaakov’s brother, Zechariah, was one of the founders of Hitahadut Hatemanim (the Union/Organization of Yemenites in the land of Israel) that was established in 1923. He was also a member of the 1st Knesset (the Israeli Parliament) between 1949 – 1951.

In his memoirs, Yaakov criticized the Yemenite community for down playing the assistance given by the Union to the community, here and in Yemen, and expressed his frustration.

Yaakov (ben David) Gluska – History of Yaakov – Part 4 page 203

“…. It surprises me that in most of the books that were published by our brothers who emigrated from Yemen, they praise and endorse Yavnieli and the Histadrut (the general organization of the workers)…(and) give them the credit for the immigration of our brothers, the Jews of Yemen from the Diaspora…

…and ignore the part of the Yemenite Organization…. and the struggles it had against the “Histadrut” for every certificate for immigration.

They do not mention that the ‘Hitahadut’ (Union of Yemenite Jews) brought 36000 immigrants, apart from the orphan children for whom it received special certificates. The High Commissioner agreed to give these certificates only after it was promised that they (the children) would be taken care of among Jewish Yemenite families.

They did not write in their books that owing to Zecharia Gluska’s intervention, the High Commissioner allowed old Yemenites to immigrate…

…they did not write about the part of the “Hitahadut’ regarding the “On Wings of Eagle” operation. They did not know or they ignored the fact that at that time the Jewish Agency said that if we would not help with this issue, they would not be able to do anything.

They did not write how the “Hitahadut” assisted them (the immigrants) at the beginning, when they came and how it supplied them with temporary shelters and food until those (in the administration) made a decision where to send them….

…they did not write in their books about the financial help that the “Hitahadut” sent across Yemen, especially to the capital Sana’a… and all of this was ignored in order to find favor in the eyes of the establishments and also because of narrow mindedness and belittling what was done by the “Hitahadut” of the Yemenites…. and this is contrary (to what ought to have been), they should have been proud that their brothers did what they did, even without resources and without any help from the Yemenite community as a whole….”

Elyashiv – first steps in the first Yemenite moshav in Israel

Moshav Elyashiv, in the center of the Sharon, was established in 1933. It sat on about 900 dunam of land (currently on 600 dunam) which was bought in 1929. The purchase was completed, after a great deal of effort, with the help of funds from Jews of Canada. At the time Bedouins from the Huwarat tribe rented the land and they did not want to leave.

The year 1929 was characterized by turbulence across the land of Israel in the context of the Arab-Jewish conflict. During this year, riots against the Jews took place throughout the country, with the main hot spots in Hebron, Jaffa, Jerusalem, and the Galilee. The Zionist Organizations dedicated to agricultural settlement did not want to add another element to the unrest and decided to wait before settling the area until the turbulence calmed down.

In 1933 the first group settled in the area following the decision of the Mandatory court to compensate the Arab tenants and confirm the legality of KKL’s right to the land and the settlement there. The Arabs were allowed to stay for six months on 200 dunam for the purpose of organizing themselves.

The candidates for settlement were all members of the Shabazi organization, established by the Yemenite Hitahadut (union) to encourage agricultural settlement of the Yemenites in an independent Moshav. Those who joined the organization paid a sum of £ 25 each. This was considered a substantial amount for that period when the average wage of a daily laborer was 25 grush.

Fifty families registered for settlement in the Moshav out of the planned hundred. Most of them were from Petah Tikva and Rishon Lezion.

Already in 1930 the establishment had started a number of agricultural settlements in this area, which was part of Emek Hefer, like Kibbutz Ein HaHoresh, Moshav Avihayil, Kfar Vitkin, Givat Haim.

In November 1933, the first 20 members immigrated to Elyashiv. The first night they slept outdoors. The next day, they erected the first hut on top of the hill. The hut had two small rooms and a large third room. They elected a committee to represent them in meetings with the various institutions for negotiations and for all administrative activities. Among the members it was decided that some of the agriculture activity would be collaborative and the some would be private. During the initial phase of land preparation and the establishment of the Moshav, the members were employed by the Jewish Agency.

Preliminary equipment for preparation of the fields was purchased from registration money that they had put into a joint account. They bought a horse, a plow, seeds and everything that was needed for a common farm.

In the first period, water was drawn from wells near a swamp beside the neighboring Arab village. It was necessary to boil the water since it was not clean. In some cases even after boiling the water was not usable for drinking.

Living conditions in the first years were difficult in terms of housing, economy, health and mobility. Relations with the Arab neighbors followed ups and downs according to the intensity of political activity and the awakening of Arab nationalism that opposed Zionist settlement.

There was no basic infrastructure and no proper transportation to and from the area.

The overcrowding, until they each built their own homes, and the lack of running water resulted in poor conditions which in turn led to the development of eye diseases and malaria.

Their difficulties were alleviated by the good will of Dr. Haim Sheba (Dr. Litza Shiber) who later founded the Sheba Hospital in Tel Hashomer. He was appointed by the administration as the regional doctor for Hefer Valley and provided medical services to all settlements in the area. All his life, Dr. Sheba did not take private money for his services, even if it was treatment at the client’s home, at night or on Saturdays, as a result of an incident in Elyashiv during his early period as a doctor.

His friend, Max Tanai, tells the following story: “The people of Elyashiv were Sabbath-keepers. There was no telephone, there were no cars. They had an agreement with Litza (the doctor) that, in the case of emergencies, they would wave a flag that could be seen for quite a distance. And this would be the sign that he was to come. But there was never a Shabbat that the flag wasn’t raised. And not always for urgent cases. Somebody had a stomach ache, a child had a toothache. So the [neighboring] kibbutz decided to charge a payment for each Shabbat request to visit the Moshav. I don’t know if it was one shilling or less. And indeed, the nuisance calls stopped because the people of Elyashiv were concerned about money. They were so worried that when a pregnant woman didn’t feel well on Shabbat [they decided] that they would wait until Sunday [the new week]. The woman died. Then Litza promised himself that he would never take profit for his services.” [from ‘Elyashiv, by Yosef Danin].

The settlers were able to dig the first water well only in 1934, after parcellation of the land. At that time an infrastructure was built for the flow of water to the top of the hill where a temporary storage pool was built.

Their land was divided into lots that were assigned to the families. Each family owned its grove and a parcel of land for seasonal growth of vegetables. A place for cattle and chickens was also dedicated.

By 1939, six years after arrival, the Moshav contained about 50 families and was on a definite route for success.

Joy – Yemenite Jews settling in Jaffa and Tel-Aviv

The fist Jewish Yemenite neighborhood in the area of Jaffa was ‘Mahane Yehuda’, established in 1903. It was built on land that was purchased earlier, in 1886, by an affluent Sephardic Jew named Aharon Shlush.

Slush was a descendent of a family that was forced to leave Spain during the 1492 expulsion. He came to own a large amount of land that was eventually used for neighborhoods north/east of Jaffa. These new Jewish neighborhoods included Neve Tzedek in 1885 and Neve Shalom in 1890.

Short background

The two-year war in Palestine between Napoleon Bonaparte and the Ottoman Empire (1799-1801) left Jaffa wounded, among other places along the shore.

After the war, the port and the market in the city were rebuilt by Muhammad Abu Nabbut Agha who was the governor of Jaffa and Gaza on behalf of the Ottoman Empire during the early 19th century. The port was then the main gateway to the country for Jewish immigrants and others, such as the Christian pilgrims.

In 1838 a group of immigrants from Morocco arrived. It triggered Sir Moses Montefiore, in 1839, to call for a census of the Jews in Jaffa. The results showed that Jews from Constantinople (Kushta), Izmir, Saloniki, Bosnia, Egypt, Bulgaria and Yemen lived in the city.

The growth of the Yemenite Jewish Community in Jaffa

The community of Yemenite Jews in Jaffa grew slowly. Prior to the 1881 immigration only individuals and a few families settled in the city. By 1904 there were over 290 members, about 72 of them born in Jaffa. (Smilanski “Haomer”, vol.1 book A)

Other neighborhoods nearby were built, such as: ‘Mahane Yosef’ in 1904, ‘Kerem Hatemanim’ in 1909 and ‘Mahane Israel’ in 1910, which were some of the early neighborhoods in the newly established city of Tel Aviv. Later ‘Shchunat Ezra’ was developed in 1933 and ‘Shchunat Hatikva’ in 1935.

Later, between 1940-8, other neighborhoods were created like: ‘Macabbi’, ’Givat Shimshon’, ‘Kfar Shalem’, ‘Givat Amal’ Alef and Beit.

The towns and villages in the center, unlike Jerusalem, offered the new immigrants more variety and more work due to the faster growing population. The Yemenite Jews were willing to take on any occupation that was offered. They were prepared to work as assistant shoemakers, tailors, carpenters, in factories, building houses or giving services.

Still, life was difficult. They lived in small sheds or improvised houses, with husbands and wives going to work for long hours. Even the children, boys and girls, went out to work. Money was short.

First Steps towards Organization within the Community

In 1903 the Yemenite community in Jaffa established a union called ‘Peulat Sachir’ (Action of the Employee). There was already a union in Jerusalem with the same name and attempts to unite the two bodies failed.

The purpose for this union was to upgrade their conditions. They rejected the beggar mentality and discouraged any member who did not have an active approach to work. They forced their members to speak Hebrew. They connected to the Zionist organization “Hovevei Tzion” and declared that they embraced the Zionist agenda. They also wanted to work in the agricultural settlements. This was an attempt that was not particularly successful since the farmers preferred the Arab workers who were more experienced in field work.

Interaction with a variety of people from different parts of the world, each with their own codes of behavior, had an effect on the Jewish Yemenite community in Jaffa.

In 1910 a different union was created in Jaffa by a portion of the Yemenite Jewish community. It was called “the Brothers’ Union”. Its agenda was more communal than national. Two years later, in 1913, three more unions were created. A group called ‘Tzeirei Hamizrach’ (the Youngsters of the East), whose members were from central Yemen, wanted to absorb a European style of life. A different part of the community, which wanted to maintain a more traditional Yemenite lifestyle, created another union that was called “Tzeirei Israel” (the Youngsters of Israel). A third group, which was not satisfied with either of the previous ones, created a union and called itself “Tzeirei Sana’a” (the Youngsters of Sana’a).

Evacuation and Return

On the eve of the 1st WW, many residents of Jaffa left it, some of them under the Turks orders. The city was a strategic spot due to its location and its port and the Turks were concerned about the loyalty of the different communities. Others left because they did not want to be recruited into the army or into forced labor by the Ottomans. Families left in a rush and took whatever they could of their belonging. They were divided up and placed in different settlements in the country in areas like Tiberias, Zichron Yaakov, Petach Tikva, and Kfar Saba. The immigration administration was moved to Petach Tikva. In Tiberias the families lived outside. The establishment was not ready for the sudden influx of refugees and was able to supply them only with flour. They lived in huts and with poor conditions. It was only when England entered the country that they, whoever managed to stay alive, were able to return back to where they had lived.

***

You can also find our videos on our Wysinfo Youtube channel.