Page Content

- Visit to Mar Saba Monastery – Video from 1982

- About the Monastery

- Visit to Mar Saba Monastery – Traveller’s notes from 1882

The Mar Saba Monastery, named after Saint Sabas (St. Saba) of Cappadocia, is a 5th Century Greek Orthodox Monastery.

Question: Where is Mar Saba Monastery?

Answer: The Mar Saba Monastery is located half way between Jerusalem and the Dead Sea, in the heart of the Judean Hills. It is built on cliffs overlooking the Kidron valley, in the Judean desert.

Mar Saba is reputed to be one of the oldest Monasteries still inhabited by monks. This continued presence throughout the years is noteworthy since the Monastery was invaded and damaged a number of times in the course of its history and each time was re-built. The Persian invasion of 614 CE, in particular, resulted in the massacre of many monks whose skulls are still kept within the Monastery as a reminder of their martyrdom.

Video Inside Mar Saba Monastery (From Wysinfo Archives)

Video (4 min 48 sec) of a tour of Mar Saba Monastery filmed in 1982, reproduced from original source material from WysInfo Archives.

©Copyright wysinfo.com All Rights Reserved

The background music for the video is the Agni Parthene, chanted by the Monks from the Monastery of Simonos Petra, and by Nana Peradze and the Georgian Harmony Choir.

Background music compliments of Milan Records

About the Monastery

The Monastery is known, among other things, for the Typicon of Saint Sabas, which influenced the order of services and prayers used in the Eastern Orthodox Churches.

It is traditionally believed that Saint Saba founded the Monastery, however James Kean (see excerpt below), and other scholars, suggested that that the Monastery may have been founded by Saba’s teacher, St. Euthymius. Saint Saba, nevertheless, was the primary influence over its development and also founded several other Monasteries in the area.

The isolated location, the proximity to the Kidron stream and the geological structure that resulted in the creation of many natural caves, provided excellent conditions for Monastic existence. In these caves St. Saba and his followers found their home in the early years of their hermitage.

The cross shown in the picture on the right marks the location of the cave where St. Saba spent his first years in the area. With time, other monks joined them and helped to create the foundations of the Mar Saba Monastery.

Saint Saba was buried on the grounds of the Monastery but his bones were removed to Venice in the 12th Century, and then returned again to Mar Saba in 1965.

The dome marking the original grave of St. Saba is seen as bright turquoise in the video presented above (filmed in 1982). The structure was renovated after the filming of the video and a golden dome replaced the turquoise

Throughout the years women were forbidden to enter the main compound and were only allowed within one building, referred to as the ‘Women’s Tower’.

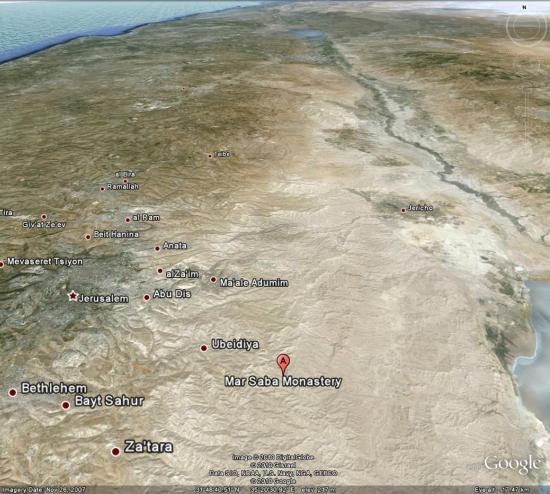

In the Google Earth map, below, you see the location of the Mar Saba Monastery, with the Dead Sea on the right, the Mediterranean Sea on the left, and the Sea of Galilee in the distance at the top. From the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea, you can see the Jordan River that runs along the Jordan Valley.

19th Century Travel Notes – Visit to Mar Saba Monastery

From James Kean M.A.,

Among the Holy Places, T.Fisher Unwin Paternoster Square, MDCCCXCI

In 1882 Rev. James Kean, M. A., B.D. made a pilgrimage to the holy land and published a book of his travel notes. The excerpt reproduced below describes his visit to the Mar Saba Monastery located in the Judean desert beside the Dead Sea.

The description of the Monastery, provided by Reverend Kean, very closely resembles a similar tour to Mar Saba exactly 100 years later, in 1982, by the Wysinfo team (see video clip above).

“Still forward, and far on in a secluded hollow you suddenly come upon a solitary hut. In front of it stands a dreadful creature, an old man, clad in a soiled white frock, with some sort of girdle twisted round his waist. In the girdle are stuck two large pistols, bright as if from constant use. This man stands mute and motionless as you approach. You shudder at the bare thought of being here alone; but, one of four, you are quite bold. He is evidently a man of few words, and disinclined to be troubled; for, when questioned as to the route [to Mar Saba], he merely indicates with a lazy wave of the hand, that it lies up the glen to the north.”

“Up this next ridge proves a stiff pull, but you are rewarded with a glorious view of the Dead Sea from the summit: it lies peacefully below, not very far off, to the east. The cliffs along its eastern shore are distinctly visible: the quietness of the scene gives them an air of solemnity.”

(Photo from Wikipedia )

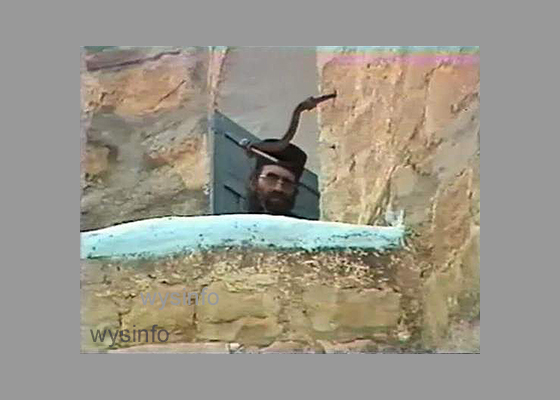

“Forced to turn westward, the range being too steep to be descended on the north, you come upon a long gradual slope downwards to the dry bed of a stream. All the way down this slope are broad patches of red anemones, at the cheering sight of which the beasts take fresh courage. It is now but a little way to Mar Saba: a few turns, and you ride down a glen, whose lower or eastern end is filled up with buildings. Knocking at a small iron door in the wall, you are answered by a man who looks down from a square tower at the north side of the door: and in a few minutes you enter the precincts of the monastery. Never were you more glad to find a place of rest and refreshment.”

“This monastery is said to have been founded in the fifth century by a certain St. Euthymius. Sabas was a pupil of his. The history of the place, as also of the man whose name it bears, is very vague. Sabas, it seems, died about 530, after having founded several monasteries, and distinguished himself –zealous man–as a stout opponent of the Monophysites, that is, the heretics who held that Christ had only one nature–the Divine. The place has been repeatedly plundered; and in consequence it became necessary to fortify it. For the last half- century [written at end of 19th Century] it has been in the hands of the Russians, who restored and enlarged it.”

“Of more interest to you at present than these somewhat isolated historical facts is the question of the material resources of the establishment. To say that you are thirsty would be to use a very inadequate expression: your tongue is like a piece of hard wood. You trot down the stair, then, without delay: through a second doorway, and down another stair: across a paved court; up a stair on the south side, and so into the refectory or dining-room. This is a large, handsome hall, fitted with broad divans all round. Here you tumble down your aching bones, and eagerly watch for the return of the little monk who has gone to fetch some wine. Thankful would you be, beyond all words, could you have a glass of spring water; but they have nothing but the stagnant tank stuff, the same as at Jerusalem; and that you cannot drink. Nor does this decanter of wine look at all inviting: it utterly lacks sparkle, and bears the stamp of being amateur-made. This, in fact, it turns out to be: they make it here, from their own vineyards. Not that there are vineyards about: the monastery possesses lands elsewhere.”

“Unpalatable as the liquor is, you are fain to have a draught. All you can say about it, however, is that it is better than nothing at all: it wets the parched tongue, and gives partial relief. But your guides disdain such trashy tipple: they have been here before, and know that the cellars can produce something more potent than drumly white wine: a liqueur of the nature of whisky is what they order up. Out of curiosity you wish to taste this spirit; but you at once regret you did not let it alone, for this peppermint sort of essence with which it is flavoured is peculiarly nauseous, and threatens to stick to you permanently. The monk does not exactly sell spirits, but he looks for a fair price, all the same.”

“The monastery lies at the mouth of a glen, just where that glen runs through the west side of a much larger glen. This latter is the Kidron valley, which here runs south, and is of immense depth–some six hundred feet. The mouth of the smaller valley, or, in other words, the open in the west side of the Kidron valley, is walled across with very strong stone-work, buttressed, to keep it from falling into the deep Kidron. Inside this wall, the smaller valley has been, so far, levelled up; and the land sides–north and south–as well as the upper reach of this small valley, have been protected with strong walls. The area of the place, therefore, is triangular, the apex side pointing to the west, and the base lying against the west rise in succession on the north and south sides. As for the Kidron wall, it rises only to about the level of the paved court; and you look over it, down into the abyss.”

“In the centre of the paved court stands a richly decorated shrine, a dome-roofed, arbour-like little structure. This, the monk who guides you over the place is eager to have you take note, contains the empty tomb of St. Saba. You think you can hardly be hearing rightly, when he says ’empty tomb’, the man’s enthusiasm being quite out of keeping with such an idea: it is empty, however, the saint’s body, or bones, having been removed to Venice long ago.”

“From this shrine you turn and go a few paces towards the north-west, and enter the rock-hewn church of St. Nicholas. This is a ghastly place: skulls in considerable numbers stare at you from behind gratings in the walls, the skulls of the inmates murdered by the Persians who sacked the monastery so long ago as about the year six hundred.”

“Another church, a much finer one, stands east of the shrine. This contains a number of pictures, after the manner of the Eastern Church. On the north side of this church are the quarters set apart for pilgrims. Here you wander up and down flights of steps, and along galleries, looking down upon lower galleries, and altogether gathering the impression of doing a civilian barracks overhanging a precipice, or, in view of the birds that come here to be fed, a lighthouse on some lonely rock.”

“Returning to the paved court, you pass to the south side as if going again to the dining-hall. You keep nearer to the buttressed wall, however, and ascend a stair which leads to the rock-hewn cells in the cliffs overhanging the Kidron. Here is the saint’s grotto, a small low-roofed den; and beyond it is a still smaller one called the lion’s grotto. The absurd story runs that Sabas, on entering his grotto one day, found it tenanted by a lion. The saint betook himself to repeating his prayers as hard as he could; but the lion, quite regardless of this pious proceeding, dragged him out twice. Nothing daunted, the saint came in again; and at last a Modus Vivendi, or mutual arrangement, was arrived at, the lion undertaking to keep to his own corner. These dens are not inhabited now: they are show-rooms, and a good deal of attention has been bestowed upon them, in the way of decoration, by holy hands in the days of old….”

Read more about the findings of early Christianity in the area of the Dead Sea…