Page Content

- Early Biblical Times

- The Ancient Perfume Industry

- Where Spices and Perfume Plants were Grown

- Early Experiments in Cultivating Plants for Perfume

- Persimmon – The Lost Scent

- Frankincense and Myrrh

- The Ancient Network of Trade Routes

- The Main Road of the Incense Route

- Who were the Nabataeans?

The Perfume Route of Early Biblical Times

The production and trade of perfume and incense was a tremendous source of wealth and consequently power as far back as the 13th century BCE – early biblical times. Merchants from the ancient Arabian Peninsula, who were prepared to weather the challenges and obstacles along a difficult trade route to the west, emerged as some of the wealthiest businessmen of their times.

They found markets among the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Mesopotamia and Assyria. These markets were filled with buyers who were willing to pay high prices for body oils used for seduction and erotica, and aromatic incense used for ritual ceremonies.

These needs and desires, together with the resulting industries that serviced them, gave rise to the famous “Incense Route” of ancient times – also referred to as the Perfume route.

The Ancient Incense and Perfume Industries

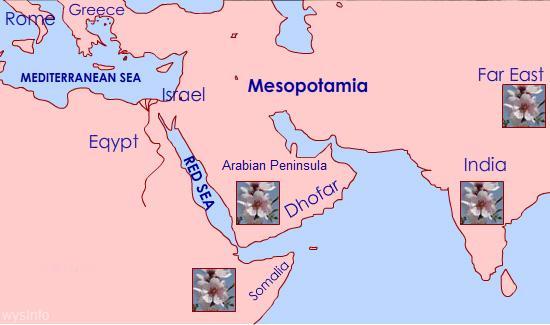

The use of perfume and scent is mentioned many times in the bible and in ancient manuscripts, with references to production sites in ancient Egypt, the land of Israel, India, Mesopotamia and in the Far East.

The importance that incense and perfume gained exceeded in many cases that of silver, gold, and precious stones.

Assyrian records from 890 BCE refer to gifts given to the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta II by the Aramaean kingdoms. In particular, balls of myrrh are mentioned among the presents.

There are also records of large quantities of frankincense and myrrh used as incense in the Jewish temple in Jerusalem, which were kept within the temple together with the King’s treasures.

Model of 2nd Temple – Israel Museum

Myrrh Resin

The merchandising of oils and incense looked, in particular, to religious ceremonies as well as the pleasure of body care for its most profitable market.

Where were Spices and Perfume Plants Grown?

Most of the spices and perfume plants were brought from the east: cinnamon from Ceylon and China; aloes from India, Spikenard – one of the more expensive perfumes plants – from Nepal and the Himalayas.

However the perfume trade concentrated mainly on Frankincense and Myrrh and both plants were grown in southern Arabia and the north of Somalia.

Early Experiments in Cultivating Plants for Perfume

The high cost of importing perfume plants, due to their rarity and to the difficulties of shipping, led some Egyptian kings, already during the 15th Century BCE, to try and grow the plants by themselves.

Queen Hatshepsut, who ruled in the early 15th century BCE, sent a royal expedition of 5 ships to the land of Punt (Somalia) in order to bring seeds and plants of Frankincense and Myrrh. This expedition is commemorated in inscriptions on the walls of her temple in Deir el-Bahri.

Myrrh seeding taken to Egypt

African myrrh commiphora abyssinica

Drawing above on left: Myrrh seeding taken to Egypt, after a relief in Queen Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri Egypt, 15th Century BCE.

The experiment was not successful; the seeds and plants did not pick up. As a result, southern Arabia established itself as the key grower of Frankincense and Myrrh, primarily in the south west of the peninsula in the mountains of Dhofar.

With its relative proximity to north Somalia, which was a main source of myrrh, and also it’s location on a crossroad, southern Arabia remained the main figure in the merchandising of perfume and spices.

This role, played by Arabia, was emphasized by Pliny, the Roman author and natural philosopher ( 23 CE – 79 CE) known as ‘Pliny The Elder’. In his writings Pliny referred to the Arabians as the wealthiest race in the world.

Persimmon – The Lost Scent

One of the most famous perfume plants was the ancient Persimmon (not to be confused with the modern persimmon fruit). The ancient plant was grown in Ein Gedi by the shore of the Dead Sea.

The process of growing the plant and manufacturing the perfume was kept a secret throughout the generations.

In 1988 a jar of oil, believed to be a rare finding of the fragrant oil of the persimmon, was discovered in the Qumran caves beside the Dead Sea in Israel.

An ancient scroll discovered in the same caves, 36 years earlier, listed the location of 60 items taken from the second Jewish Temple between 66 CE and 68 CE. The scrolls were hidden in an effort to keep these items from the approaching Roman army. There were 23 talents of persimmon oil

among the items in the caves.

Pliny, the Roman writer, historian and natural Philosopher, wrote that an amount of this perfume oil that was equal to, in today’s language, a half a liter, cost 300 dinars and could go up to a thousand.

Today, nobody knows what happened to this plant. It is believed that during the war against the Romans, in the 1st century CE, the Jews of Ein-Gedi, who did not want to reveal the secret of growing this plant and producing its unique perfume, decided to exterminate it and take its secrets with them to their graves.

Frankincense – a Tribute to the Devine

Myrrh – Perfume, Incense and Medicinal Balm

The Frankincense plant is a low small bush that generates a transparent yellowish resin from which the aromatic essence is extracted.

The resin is produced by making cuts along the stem and peeling off a small amount of the stem skin. At this point the bush generates the resin that is hardened in the stem at the bottom of the cut. After three months, the hard yellowish resin ball can be picked.

Frankincense tree boswellia sacra

Frankincense resin

Myrrh on the other hand is a tallish tree, which usually produces a reddish brown resin that is generally gathered from the trees in the summer.

African myrrh commiphora abyssinica

Myrrh stem commiphora abyssinica

With the growing demand for it, during the Roman period, a 2nd extract was made in the early spring, by small cuts made along the stem.

In preparation for shipping, the Myrrh resin was kept in leather bags in order to keep its oily constituency. The hard Frankincense resin substance, on the other hand, was packed in baskets and was handled very carefully in order to keep the resin balls and branches intact.

The Ancient Network of Perfume and Incense Trade Routes

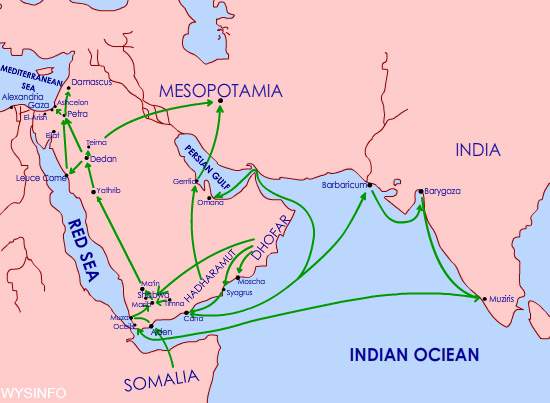

The increasing demand for spices and perfumes in the ancient world led to the development of an extensive network of trade routes, connecting the West to the East by land and by sea. These routes connected India and Arabia to Mesopotamia, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Greece and Rome.

The transportation of the merchandise followed several routes, depending on where the end destination was and corresponding to the level of security they offered.

The Main Road of the ‘Incense Route’

The desire for trade between the east and the west resulted in the rise of a number of main routes, such as the Silk Trade Route between China and Europe, and the Kings Highway from Egypt, through Aqaba up to Damascus and Assyria.

One of the primary routes of commerce, which was defined later as ‘The Incense Route’, started in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula, where some of the finer perfume plants were grown.

It went north, parallel to the Red Sea, with approximately 65 resting stations.

Map showing incense route following the Red Sea

Map showing incense route from Dedan splitting toward different directions

Towards the end of the route, at Dedan, it divided into a few different routes. One turned north eastward, toward Mesopotamia. Two other routes were directed toward the seas – both ultimately brought the perfume, spices and incense to Petra. One continued inland directly to Petra while the other turned southward to the port of Leuce Come, situated beside the east shore of the Red Sea. From there this route continued by land, also to Petra.

At Petra it split again. One route went north to Damascus, the second one went west, through Israel to Gaza and from there to Egypt or to Greece and Rome in Europe.

There was another route that went from the southern part of Arabia, through the desert, north, some 40 days of traveling, to the port city of Gerrha, in the Persian Gulf, and from there to Mesopotamia and Israel and Europe.

On land the transportation was carried mainly by camels that were domesticated already around the 12-13th century BCE.

Convoys at that period were composed of many dozens and sometimes hundreds of camels loaded with merchandise, food and water. These convoys were able to go some 15-20 kilometers a day and the whole trip from South Arabia (or what is today Yemen) to Gaza, took about half a year.

The route stretched along some 2400 kilometers, and a difficult topography was chosen in many areas in order to avoid robbers.

Fortresses and resting stations were built in strategic points along the trade routes in order to serve and protect the convoys that were carrying the expensive merchandise from robbers. These stations controlled the water sources and the security along the main and the secondary routes.

Who were the Nabataeans?

The Nabataeans, also known as the “Lords of the desert”, were inhabitants of North Arabia. They played a central role in the marketing of perfume and controlled the trade routes that stretched from Leuce Come, a port on the north east side of the Red Sea, up north to Petra; the route from Petra, west, through Israel’s Negev to Gaza in the Mediterranean; and the route north, from Petra to Damascus.

The great wealth accumulated by the Nabataeans is described by Diodorus Siculus who lived in the 1st century BCE:

“While there are many Arabian tribes who use the desert as pasture, The Nabateans far surpass the others in wealth, although they are not much more than ten thousand in number; for not a few of them are accustomed to bring down to the sea frankincense and myrrh and the most valuable kinds of spices, which they procure… from what is called Arabia…” (Diodorus Siculus,XiX:94,5).

“Diego Delso, delso.photo, License CC-BY-SA”

The Nabataeans reached their peak between the last third of the 1st century BCE and the middle of the 1st century CE.

The Nabateans set their capital in Petra, in what is today Jordan.

It is situated some 80 Kilometers south of the Dead Sea, not far from the Israeli border. The impressive shrines and palaces carved into the hard red rocks reflect the richness and wealth they experienced.

In 104 CE, the Nabataean Kingdom and its capital city, Petra, were annexed by the Romans. The fortresses and rest stations fell into the hands of the Romans as well. Extensive building projects were undertaken then, reaching a peak in the Byzantine period.

The Nabataeans, who were pagans, eventually converted to Christianity around the 3rd-4th century CE, followed by extensive buildup of churches in all of their cities. The knowledge about them is mainly extracted from Greek and Roman sources.

The Nabataeans’ two fields of expertise were merchandising and desert agriculture. They led the perfume and spice convoys in the desert and built the resting and guard stations along the routes. These stations were set at a distance of a day’s walk from each other.

It is not clear yet how and why they disappeared from the stage of history. Some believe that with the decline of the demand for perfume and spices, and subsequently the diminishing importance of the trade routes, the cities were deserted and the Nabataeans integrated with neighboring tribes.

The Cost of Transporting Perfume and Spices

Although the trade routes were well established, even during their prime the transportation of perfumes and the spices was a long and dangerous process – inland, because of the desert conditions and robbers, and at sea because of the storms and pirates.

On top of that, heavy taxes were imposed on perfume and spice shipments, especially on the overland convoys.

Pliny, The Roman writer, and natural philosopher describes this clearly: “Fixed portions of frankincense are also given to the priests and the king’s secretaries, but beside these the guards and their attendants and the gate-keepers and servants also have their pickings. Indeed, all along the route they keep on paying, at one place for water, at another for fodder or the charges for lodging at the halts and the various octrois. So that expenses mount up to 688 denarii per camel before the Mediterranean coast is reached” (Pliny Nat.Hist. XII:65) 3.

It is not surprising therefore that under such circumstances, the price of perfume and spices was so high

The great demand together with the limited supply made them so desirable, to a point where it triggered thievery even during the production and manufacturing stage

The Decline of the Perfume and Incense Trade Route

The commercial relations between the east and the west reached their peak during the 2nd Century CE. At this time the Romans succeeded in sailing directly to and from south Arabia and India, the source suppliers of spices and the raw material for perfume. As a result, the importance of the Arabian kingdoms slowly diminished since they were no longer required for the transport of the costly produce.

From the 4th century on, when Christianity became the official religion, the practice of cremation was avoided and there was a return to ordinary burials which led to a significant decrease in the demand for incense. The consumption of cosmetics for body care also diminished drastically in the Christian world, which frowned on luxuriousness and indulgence in bodily pleasures.

The trade in spices and resins used for the cosmetic industry, although diminished, did not completely cease but it never reached the same importance as during it’s grander times.

Following the Moslem conquest of the area in the 2nd half of the 7th century, and the decline in the demand of perfume in the new Christian world, the perfume trade routes died out and the cities along these routes were gradually deserted.

Read more about some of the stations along the trade route between Petra to the Mediterranean Sea.