Page Content

- The Ancient Period

- Classical Times

- The Byzantine Period and Christianity

- Islamic Period

- Middle Ages – The Perfumes of Venice and the Spread to Europe

- Modern Times

Throughout history people have found ways to surround themselves with pleasing smells – sometimes perfume for erotic arousal, and sometimes just to cover up unpleasant street and body odors.

The source of the English word “perfume” comes from the Latin phrase “through smoke” (per fumus). In Hebrew, the word “bosem”, (besamim in the plural form) is used to refer to perfume, fragrant oils as well as the fragrance used for incense.

Documents and drawings that record the use of perfume go back thousands of years before the Common Era. There is evidence of a perfume manufacturing center in Cypress dating back to 4000 BCE.

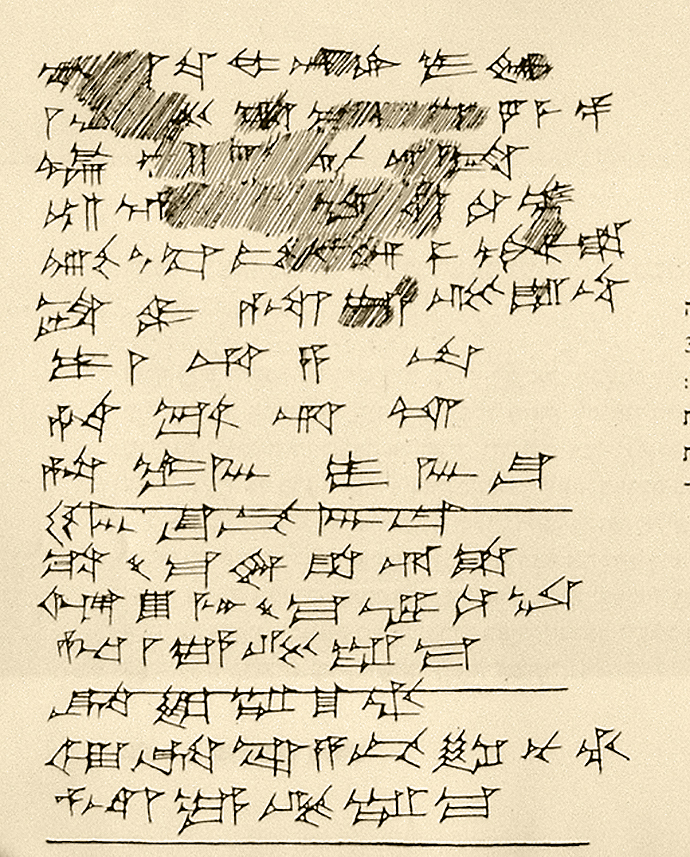

Ancient Assyrian records and Egyptian transcripts have been found that provide details about their processes for perfume making.

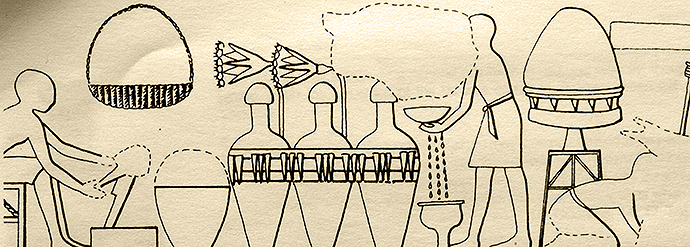

producing perfume – 350 – 450 BCE

The water lily was depicted in many ancient Egyptian drawings and wall carvings as one of the more popular aromatic flowers used for perfume.

Yet in ancient times, perfume was very different from the liquid substance we are familiar with today.

Back in ancient times perfume was manufactured as an oily or solid buttery substance. This was produced from some form of natural oil like olive, almond and sesame oils or out of animal fat. The oil was usually saturated in fragrances using elaborate methods and very specific recipes.

Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and Israel

Throughout the ages there have been different uses for perfume products. In Egypt for example, aromatic incense and perfumes were used for spiritual ceremonies in temples.

The good, sweet smells would attract the gods and repel evil spirits that were thought to bring illnesses. Bodies were buried with perfumes and aromatic ointments so that they would be welcome by the gods.

Priests were anointed daily and private people, women more often than men and higher classes more often than lower classes, tended to use flowery aromatic oils for body care. Pleasant fragrances were used in the cities to overcome the unpleasant smells from the street.

The Assyrians in Mesopotamia (located in areas that, today, are part of modern Iraq and Iran) were major perfume consumers, and a substantial industry developed there as well.

There are also countless references to perfumery and aromatic oils in the bible.

Perfume substances in Israel were used primarily for incense and ointments required for the temple, as well as by the rich for pleasure and body care.

Perfume manufacturers in Israel were presumably located in En-Gedi and En-Boqeq where they specialized in the production of perfume from an ancient Persimmon plant (not to be confused with the modern plant known by this name).

The perfume from this plant was produced through a unique process that was kept secret by the producing families. The Persimmon plant (called apharsimon in Hebrew) and the knowledge of how to manufacture the perfume from it were lost together with the defeat of the Jewish state by the Romans around 70 CE.

Mosaic in Ein Gedi archeological site

Ein Gedi Falls

Pressing

The earliest process of perfume production that has been discovered is pressing.

With the pressing method plants were crushed and then pressed, much like the production of oil or wine at the time.

Olive press in Neot Kedumin, Israel – representing biblical period

Olive oil press in Neot Kedumin

Later on the process evolved and developed, particularly in Egypt. Paintings and wall carvings show the plants being placed in a sheet of cloth and twisted until the aromatic materials were drained from the source.

perfume from aromatic plants.

This process, however, was relatively ineffective and was eventually replaced during the classical period.

Cold Steeping

Another method of processing included cold steeping, which is effective with only certain kinds of flowers, but not with all plants. The process involves saturating and pressing together the plants with a layer of animal fat, replacing the plants daily until the fragrance is fully absorbed in the fat. The outcome was scented pomade (a perfumed ointment).

Similar methods were used up until the 20th century when the substance was soaked in ethanol in order to dissolve the residue of the fat and leave a cleaner/purer substance rather than a waxy/buttery mixture.

Hot Steeping

A third method was hot steeping which was a similar process to cold steeping only the plants were pre-treated with a special astringent and saturated in water or wine. This helped the absorption of the scents in the base oil. Later the mixture was repeatedly heated, left to rest and then strained.

Perfume During Classical Times

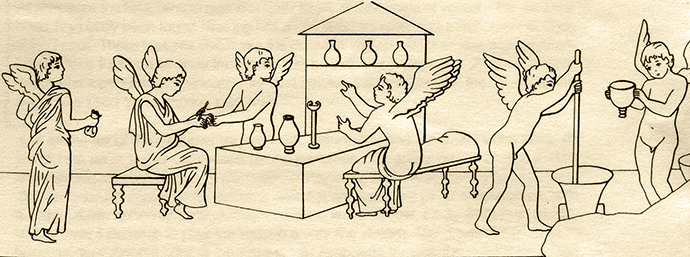

In Greece the gods were credited for teaching the art of perfumery. The different fragrances were also part of the gods’ doings, for example there is a myth that claims that Cupid’s encounter with the rose gave it its scent, and similarly other fragrances were associated with other gods.

Rose – associated with myth of Cupid

Cupid – photo by Ricardo Andre’ Frantz

Perfume was directly connected to beauty, art and attraction, with legend claiming that Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty and love, was the first to ever use it. Perfumes were often named after the Greek goddesses.

When Alexander the great conquered Arabia (3rd century BCE) he sent back huge shipments of spice, incense and plants for perfume making.

The industry grew in the Hellenic area, and at a certain point the use of perfume became almost exaggerated — to the extent that Solon, an Athenian statesman, viewed it as a threat and, in order to limit its use, prohibited its sale. This law was abandoned shortly afterwards due to the public’s rejection of it.

Excerpts from the writings of the Greek philosopher and scientist Theophrastus (c. 371 – 287 BCE) include discussions about scent, their origins and the affect they have on man’s moods and thoughts. He also wrote about the connection between odor and taste – which is commonly accepted today as important for understanding our perception of smells.

Ancient Greek Perfume Manufacturers

Greece’s contribution to the industry was great. This is not surprising since a daily bath was an important activity for Greek citizens (and then later, for the Romans).

This ritual included the abundant use of perfumes – there is even some evidence that different scents were reserved for different parts of the body.

It is believed that the Greeks were the first manufacturers of liquid perfume (although not the liquid perfume that we know today).

Classical Greece saw the beginning of a distillation process where aromatic plants were steeped in hot or cold oils.

While it is difficult to find information about the Greek methods for manufacturing perfume, there are at least two Greeks who left behind interesting writings.

Theophrastus (c. 371 – 287 BCE) was a Greek metaphysician who wrote about aromatic plants. Details about actual perfume recipes were provided by Dioscorides (c. 40 – 90 CE) a Greek physician who lived and wrote in Rome during the time of Nero. He described a common manufacturing process which involved two stages. The following excerpt refers to the writings of both Theophrastus & Dioscorides:

“Two stages are involved, the first, stypsis, served to prepare the oil by the addition of weakly-scented astringents such as aspalathus, cyperus and ginger-grass. This treatment did not permanently scent the oil, but rather made it more receptive to the stronger fragrances which would follow… It also served incidentally to thicken the oil somewhat. The astringents were mixed with wine or water to form a paste, then heated in the oil.

Theophrastus comments that this preliminary treatment was recommended in most cases, but was particularly necessary with olive oil, which does not retain odors well, and with volatile perfumes like rose. In the second stage of manufacture, the treated oil was given its final fragrance. This process too involved the steeping of aromatics. Repeatedly the oil was strained from one vessel into another, and fresh batches or aromatics were added until the perfume reached the desired strength, sometimes only after several days”1.

1.The perfume Industry of Mycenaean Pylos, page 13 – By Cynthia Wright Shelmerdine. Publisher: Goteborg:P. Astorms Forlag, 1985.

Some of the most commonly used fragrances of the Greeks were rose, saffron, frankincense, myrrh, violets, spikenard, cinnamon and cedar wood.

The following is a recipe for iris perfume attributed to Dioscorides of the 1st century CE in his book “De Materia Medica” (I.56)

“Take 9 litrae 5 unciae [about 3.1 kg.] of oil and 6 litrae 8 unciae [about 2.2 kg] o f spathe, chopped as fine as possible; mix with 10 kotulai [about 0.25 l.] of water, put into a cauldron and boil until the mixture absorbs the scent. Then strain it out into a mixing-bowl smeared with honey. From this scented oil the first iris perfume is made by steeping iris [root] in the treated oil, as indicated below.

Others; as indicated, chop 5 litrae 2 unciae [about 1.7 kg.] of balsam-wood and boil together with 9 litrae 5 unciae [about 3.1 kg.] of oil. Then remove the balsam-wood and add 9 litrae 10 unciae [about 3.2 kg.] of sweet-flag, steeping a lump of myrrh in sweet old wine. Then in 14 litrae [about 4.6 kg.] of the treated and scented oil steep an equal weight of chopped iris [root]; leave it for two days and two nights, and then strain it out forcibly and vigorously. And if you want it stronger, steep and strain out an equal amount twice and three times in the same way.”2

2.The perfume Industry of Mycenaean Pylos, page 14 – By Cynthia Wright Shelmerdine. Publisher: Goteborg:P. Astorms Forlag, 1985.

The Romans

The infatuation with perfume spread westward through the Mediterranean to the more distant outskirts of Europe.

Soon Rome, France and Spain became a part of this ever growing industry. Rome, with its natural tendency for extravagance and abundance, embraced the coming fragranced revolution and incorporated it in their decadent everyday life style. Stories were told about perfumed doves that were set out above the heads of diners in order to fill a room with aroma.

Perfumes from Greece and Asia were brought to Rome by Julius Caesar, Heliogabale and Nero who, it was claimed, burned more incense than Arabia could produce. This attraction to such products didn’t stop with perfume but went on to include all forms of beauty products – creams, ointments and remedies – which were available for the higher classes as a sign of wealth and fashion.

The Romans also made interesting contributions to the development of the industry. Pliny the Elder, a natural philosopher and author (~ 23 CE – 79 CE) outlined a primitive method of condensation which collected oil from rosin (a resin usually extracted from material such as pines) on a bed of wool.

Perfume During Early Byzantine Period

Christianity took its toll on the perfume industry of the region as it rejected the vanity and excess of ancient Rome and Greece. Yet it did not rid itself of its benefits entirely. The use of incense was still taking place as part of religious ritual.

In fact, the Christian bible was full of references to fragrant material such as frankincense and myrrh (gifts of value to Jesus at his birth) and both substances continued to be sought after during this period.

The higher classes were also still using perfume but to a much lesser degree. For example, Empress Zoë, in the Christian stronghold of Constantinople, was known to employ court perfumers. Despite the general decline in the use of perfume, the region continued to play a role in the perfume industry throughout the Byzantine period, and eventually this provided a base for perfume production in later periods.

Perfume During the Islamic Period

Considering that most popular ingredients for the manufacture of perfume were found primarily around the Arabian Peninsula, it is not surprising that Islamic cultures contributed significantly to this industry.

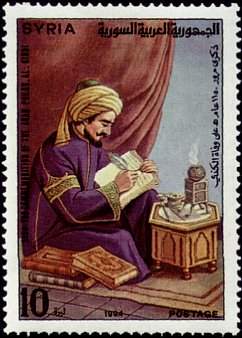

In Islamic culture, perfume usage was documented as far back as the 6th century CE. Al-Kindi (c. 801-873 CE – also known as Alkindus in the west), a Muslim Arab philosopher and scientist, is considered by many as the father of the modern perfume industry. He is known for his work in isolating alcohol and was the first to describe the production of pure distilled alcohol from the distillation of wine.

Al-Kindi invented many different scents by experimentally combining different plants and other materials in order to produce perfume products. One of his books, the Kitab Kimiya’ al-‘Itr (Book of the Chemistry of Perfume) contains recipes for fragrant oils, salves and aromatic perfume water.

Solanum jasminoides

Almond blossoms

Orchid

Orchideen zentrum celle

The process of distilling in order to extract essential oils and fragrances was perfected by the Persian physician, philosopher and alchemist (sometimes referred to as an Arabian), Avicenna, around the 11th century CE.

Middle Ages – The Perfumes of Venice and the Spread to Europe

Venice was an important center for trade between the west and the east, and became the main channel through which the raw materials for incense and perfume reached Europe. It continued to play a primary role in the industry, within Europe, for a few hundred years.

While distillation was already known in the 11th century (from the Islamic world), many European scientists became fascinated with the process around the 13th and 14th century. They were determined to separate the ‘essential ‘ from the ‘non-essential’ parts of a compound.

The perfume industry around this time (approximately 1300 CE) benefited as a result of all this activity, and the fragrance production center of Grasse, in the south of France, began to develop.

During this period the Black Plague, dated from 1347 CE to 1351 CE, began to take its toll. A practice emerged of enveloping the dead bodies in the smoke of incense, with the hope that this would ward off further death. In addition, torch bearers used fragrant herbs as a means for clearing the way for important and rich people.

Perfume and the Early Renaissance

The various crusades that stirred Europe (11th century to the end of the 13th century) lured European knights into the Holy Land, resulting in the interesting additional consequence of stimulating the perfume industries of Europe.

In 1370 the first alcohol-based perfume was created for Queen Elizabeth of Hungary who was known for her famous toilet water – also referred to as Hungary Water. The primary ingredient of this toilet water, it was claimed, was rosemary. Some have argued that this was the secret to Queen Elizabeth’s beautiful skin, which she retained into old age.

Perfumes during the early Renaissance period were primarily used for neutralizing the natural scent of leather accessories such as gloves, handbags and leather jackets (often made out of goat leather that the moors would import through Spain).

Painting of Crusaders

Catherine de’ Medici, attributed to François Clouet, c. 1555

“Les Maitres Gantiers” (masters in glove making) single handedly took over the fragrance industry and, at a certain point, were the only ones permitted by the king (as a result of a royal decree, April 4 1573) to make and trade fragrances. Their name eventually changed in the 17th century from Master Glove Makers to Master Perfumers.

There were other uses for fragranced products. When Catherine De Medici, known as the ambassador of perfume, moved to France from Italy to marry Henry II, she brought her perfumer, René le Florentin, with her.

René created, among other things, poisonous jewelry for the new queen to use against her enemies. Together with the poisonous jewelry, he also made her scented gloves that would mask the scent of the poison. It was rumored that he had a lab that directly connected to her apartments by a secret route. This was apparently to ensure that no perfume recipes could be stolen or copied. He later moved on to open an incredibly successful perfume store in Paris.

Major factories were constructed in Montpellier where about 100,000 acres were used for the cultivation of flowers for perfume use.

The importance of perfumers grew together with the extravagance of their rich and noble consumers. Most productions, however, came to a halt when the French revolution occurred. The attack on the aristocracy, and the strong association of perfume with that class, led many manufactures to cease their work. The industry re-emerged with the rise of Napoleon, who was happy to adopt many of the habits of the old aristocracy. Some of the companies that developed during this time still exist today.

In the early 1800s, perfumers started to use a much higher degree of alcohol in an effort to maximize the process of making perfume. Another major step, which dramatically affected the perfume industry, was the first attempt to reproduce synthetically the scent of some fruits and plants. These innovations enabled the creation of modern day perfumes.

The Perfume Industry of Modern Times

The 19th century saw a rejuvenation of the perfume industry – to a large extent as a result of the discovery of synthetic imitations of natural essences. For example, towards the end of the century the first synthetically reproduced scents of plants and fruits were created by French and German manufacturers, Schimmel and Haarman & Reimer (H&R).

This period brought revolutionary new synthetic scents such as:

1869 – heliotropine

1877 – coumarin

1888 – artificial musk

1890 – vanillin

1890 – ionone

1905 – l’hydroxycitronellal

The industrial revolution (late 19th century/early 20th century) obviously also had a tremendous impact owing to new methods of mass production, better transportation and communication. This enabled perfumers to manufacture new forms of perfumes that were easier to produce, easier to deliver and therefore cheaper. Suddenly perfumes, which were once enjoyed only by the upper classes and the wealthy, were now accessible to any housewife or shop girl.

While modern perfumes are, to a large extent, synthetic imitations of ancient perfume scents (and sometimes synthetic innovations providing brand new scents), one can still find original natural ingredients among them. The following list provides examples of ingredients of interest (both synthetic and natural) that are used within some of the well known fragrances.

Notable natural ingredients & some modern perfumes that use them:

| Natural Ingredients | Examples of Fragrances that use these ingredients |

Frankincense –

Used since ancient times, adding a fresh, woody, slightly spicy and fruity scent

Myrrh –

Also used since ancient times, adding a strong bitter scent.

Patchouli –

Of the mint family, adding an aromatic woody scent

Notable synthetic ingredients & some modern perfumes that use them:

| Synthetic Ingredients | Examples of Fragrances that use these ingredients |

Aldehyde –

A purely artificial scent that does not mimic any natural scent. This synthetic ingredient became famous in 1921 with the first appearance of Chanel No.5 (which still combines aldehyde with natural ingredients such as the famous Rosa Centifolia).

Amber –

Mimicking the scent of the ambergris which is a natural ingredient derived from sperm whales.

Artificial musk –

Mimicking the scent of natural musk which is a natural ingredient obtained from a gland of the male musk deer.

With all of the changes in the modern lifestyle, perfume became less of a means for masking lack of personal cleanliness and more of a fashion statement.

While there are many benefits to the industrialization of the process, the modern perfume industry has introduced ingredients that have nothing to do with the smell of the perfume.

Among other things, modern perfume usually includes coloring agents, anti-oxidants and other chemicals that are added in order to catch attention or to improve shelf life of the perfume. Unfortunately, many of these ingredients are allergens.

While not everyone is allergic to fragrances, people should be aware of the possibility of this type of allergy and should learn to choose products based on their body’s reactions.